The blog of Iain M Spardagus

Freedom of mind and freedom of expression are the bedrock of human society.

It is a month, almost to the day, since my daughter and her partner moved out of this little house.

She had been living with me for 13 years, half her life, since her mother left to live and work in the US. Her partner, G, had come to live with us four years ago, in rather extraordinary circumstances that I do not need to go into but, in 2020, COVID brought new restrictions for everyone (except, it seems, Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings) and, by the time those ended, his presence in the house had become an established fact.

We actually rubbed along quite well but it did not prevent a certain level of curmudgeonly resentment from building in my mind. G was a good cook and liked to cook as a relaxation from his day job as a bricklayer. Up until his arrival I had been the provider of food and had achieved a level of competence in a narrow but useful range of meals, but after he moved in my role was limited to forager and banker, which I found less satisfying for all that it was still demanding.

To find resentment in someone making your life better is pretty sad but it wasn’t just the diminution in my role that I resented. Still, to list all the petty grievances that surfaced in my head over the period would serve no purpose here but to make you, the reader, squirm at my insufferable intolerance so I shall refrain from doing so but let me say that even as they arose I knew that they were simply the hooks on which I hung my ego’s discomfort.

All of which did not stop me from recounting them to anyone who would listen, most often in the pub, which I visited regularly out of what I liked to think of as a sense of duty. But as I told my tale of woe it always elicited the same response from my audience: “Throw them out. Give them notice then chuck their stuff into the garden and change the locks.” And as soon as this advice issued forth, I knew that I had done a bad thing. It was a self-serving lie.

Because it really wasn’t that bad at all. Yes, it was less than ideal but it was not their fault. They wanted a place of their own just as much as I wanted my space back. They just had nowhere else to be. And I had the room to offer them. In my heart I knew that what was happening was The Right Thing To Do. Throwing them out, even asking them to leave, even letting them know that I would like them to leave, would have been an offence against decency. So I swallowed my resentment and got on with … getting on.

Not, of course, that this put a stop to my craving for their departure, or my displeasure and the hundred and one little “inconveniences” that their presence put me to. No, these worked themselves up in my head on a daily basis until I could barely contain them.

So it was a huge relief when they announced that they were actively looking for a place to move out to and an even greater one when they found a place. I tempered my joy at their imminent departure with the thought that it was as good for them as it was for me and threw myself into helping them complete the move.

As I said at the start, it has now been a month since they moved out. And here I am, in the middle of the night, unable to sleep. And a good part of that inability is down to the unnatural quiet of my home. The almost supernatural awareness that I am alone here heightens my sensitivity to almost any sound that a house makes at night as it cools. But it is more than the sounds of silence. I no longer come down in the morning to a sofa that needs straightening because my daughter has been sitting on it. I no longer have to collect dustpans full of cement and brick dust from the lobby on a daily basis. The coatracks are empty of all but my coats and hats. The TV, which for years I regarded as under the narrow jurisdiction of my daughter’s tastes, now demonstrates to me repeatedly that there is nothing that I want to watch. “My” music, which, for years, I told myself I could not play because it would not be “appreciated”, now jars and irritates me when I switch it on.

I suppose in time I will reach a new accommodation with myself and learn again to live alone. But, for now, I am experiencing something akin to grief at the loss of the company that I had, for some time, enjoyed the luxury of believing had been imposed on me.

The truth of that old adage is glaring at me. Be careful what you wish for.

A rather trivial little poem for Earth Day 2024

What on earth gave us the right

To run the show both day and night?

Who said “we’ll take whatever’s needed”?

Oh yes, of course, we did.

What on earth made us so cocky

To drag the world down roads so rocky?

Who ignored the few who pleaded?

Oh yes, of course, we did.

What on earth do we think we’re doing

Shutting our eyes to all the ruin?

Who told us we can’t be defeated?

Oh yes, of course, we did.

What on earth can save us now?

Not fossil fuels or or sacred cows.

No, we must reap the fields we seeded.

What brought us to the brink? We did.

We had the great good fortune to study some of William Butler Yeats’ wonderful poetry at Wanstead High School in the late sixties. At the time it meant little to us and simply gave scope to schoolboy invention. I particularly recall “Who Rides with Fergus Fish” and how farts became known as “The Wind among the Reders” in honour of one of our class who was noted for them.

This one has been adapted, without permission of course, to reflect more accurately life as we know it.

Had I the heaven’s embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light;

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my jeans;

I have spread my jeans under your feet;

Tread softly because the landlady doesn’t allow visitors after ten fifteen.

I have been told on occasions that my posts are “too personal”. So here is a “trigger warning”. This contains personal stuff. I am neither proud nor ashamed of what follows. It was what it was.

She called me Schnucki. It wasn’t my real name, it had been the name of my sister’s dog. A pet name, then, in more than one sense.

At the time it just seemed charming to me. I was in love. I needed to believe she loved me. So I embraced the name as any lover would. It has only recently occurred to me that in bestowing on me the name of a pet dog she was making a point, a joke.

Oh, but she was lovely. In winter she wore long Liberty skirts over knee length black boots and a crushed velour hunting jacket over a silk blouse, In summer it was Laura Ashley print dresses (God, I’m starting to sound like Sally Rooney). She looked like a Russian princess as she strode around and I fell hopelessly in love with her.

There’s a cliché right there – “hopelessly in love”. But the thing about cliches is that they have their origins in truth. I was 31. I was still living at home. I had yet to kiss anyone other than my Mum and a few Aunties up in Sheffield (obligatory pecks on cheeks). I had “fallen in love” just once before, at the age of 15 and had managed to persuade myself that that was it, the one true love of a lifetime (I was a romantic, into Mahler and Cohen), which I managed to scupper by long bouts of brooding silence and total, platonic immobility over several years. Yes, as it awakened in me, it felt hopeless.

But somehow, this time I worked myself into a state in which I had to tell her and I did. We worked about two floors apart and one evening I went in search of her and to my utter surprise she said “Let’s go for a drink”.

In the Two Chairmen, one drink became two then three and I found myself talking, quietly but with the unexpected aura of confidence, telling her about me and then responding to what she said about herself. I knew next to nothing about her when we entered but those drinks opened us both up and she seemed genuinely to want my take on her issues while I heard myself uttering a kind of quiet savant wisdom that I hadn’t known I possessed until then.

I told her I had fallen in love with her and she suggested that we walked across the road to St James’s Park. It was dark by then. She seemed amused when I said I had never kissed a woman and suggested I should kiss her. And I found myself kissing her and felt her warm and responsive in my arms (God help me, it sounds even more like Sally Rooney now).

At some point we both realised that my hand was on her breast, something I had never done before, had never thought I could do without repelling the person I was touching, but she just laughed softly and said “Found them alright then.” And that took away all my guilt. I was in love. Everything was suddenly “as it should be”.

Then she told me about her husband.

It was beyond strange. She spoke of him with huge respect and affection and I remember thinking “Then what are you doing here with me?” But I wanted it to go on so, like Pinocchio, I knocked Jiminy Cricket off my shoulder and carried on. From now on, I was a real boy.

I think it was a few weeks later that I was introduced to him. We had all been working late and met for an after- work drink. And I liked him immediately. Not only was he clearly the most intelligent man I had ever met, he was also gentle and kind and he clearly adored her and welcomed me unquestioningly. The pangs of conscience were audible now in my head but they were not loud enough, yet, to persuade me to stop. We walked to Victoria Station and, on the pretext of having to see me to the other platform, she left him on the Westbound side and walked with me through the subway to the Eastbound platform, stopping in the middle for a passionate kiss. I saw what “shining eyes” meant. Hers were positively blazing what I was keen to read as joy.

For the next little while it was a passionate relationship. She took me to her bed and ended my virginity. No really, that’s how it was. We had taken the afternoon off and ridden the tube to the end of London where their house was. There she excused herself and went upstairs. I, naively unaware, sat on the sofa wondering how long she would be. Then after five long minutes she called down, “Well? Are you coming up?” Puzzled, I climbed the stairs and found her naked in bed. I had never seen a grown woman naked before except in photographs. She seemed entirely comfortable, however, and when she told me to get undressed I complied, in an instant setting aside all the shy reserve of thirty years (up to then I didn’t even like having the top button of my shirt undone). She told me later, in a kind of benign feedback session, that I should never leave my socks til last, it was unattractive. It was as if she was training me. I realise now that she was. I was her project.

I can’t recall much foreplay. My penis became instantly, painfully hard and, as if a program had been activated without involving me, it found her opening and slipped inside. I came immediately. She said, with no malice, just a teasing smirk, “Is that it then?”

All at once I was consumed with a panicked guilt. She read it in my face immediately and asked me what was wrong. I blurted out my fear that I had made her pregnant. She laughed, gently, and told me that she wasn’t up for taking risks like that and then explained to me about the Dutch cap that she was wearing. This was all new to me. Another learning experience. Another pair of words for my lexicon.

I was, from that time on, through all my years to come, until Finasteride and Tamsulosin relieved me of any vestige of sexual competence, a useless lover, always premature, always trying in the heat of the moment to work out how to please, never quite succeeding, always clumsy and embarrassed. But she did not complain as long as I tried. She was like a patient teacher with a backward child. We had evenings together (but never nights) and she introduced me to smoked salmon and cream cheese and champagne (“You have to love The Widow (Veuve Cliquot), such a happy champagne”, though sometimes it was Perrier Jouet with its fancy embossed bottles and once or twice pink, when strawberries were in season.)

Then there were the evenings out with both of them. They introduced me to the Cork and Bottle, then in its heyday, and I got to meet Don Hewitson and to become acceptably pretentious about wine. And the more I got to know her husband the more I liked him, which was awkward. But his gentle acceptance of me allowed me to think that maybe, just maybe, this was okay, that in some way I was making things better. I tried not to think about whether he knew or guessed what was going on and I learned instead to play the part of a flattering and appreciative friend.

Looking back now it sounds like Pygmalion with me cast as Eliza. I grew in sophistication and, like Miss Doolittle, began to believe that this newly educated version of me was the real thing, not just a social experiment.

For their part, they seemed to want my company, both of them. And through them my horizons broadened, through classical concerts, dinners, conversations, wine tastings. I say they broadened but again I now see how much of the tunnel of my life was closing behind me at the same time as it opened in front of me. My school friends now seemed dull and horribly prosaic. They had no interest in my accounts of things I had eaten and drunk and I was aware that their lives meant little to me. Things I had enjoyed now palled, no space. The same became true of my relations with my parents, who had up til then seemed so inspiring but now seemed so narrow and even judgmental (as indeed was I now, though, of course, my judgmentalism was righteous).

But all that mattered at the time was the approval of this woman and her husband. For that I learned to shine before their shiny friends and to enhance any social gathering they took me to. She said to me one time after I had risen early to tidy the last night’s abandoned party “Schnucki, you are the perfect house guest.”

But I was learning something else too, something that a perfect house guest must never lose sight of: that you are at best an adjunct, an accessory. Never believe that you are more than a part of their story, an anecdote, an amuse bouche for their table.

I had become aware that I was not her only lover. She had at least one and sometimes more than one other. And much as it hurt me to realise it, I saw that I was not even Number One lover. But such was my fear of losing her, of losing what she allowed me, that I took this on board even to the extent of becoming her confidant and counsellor as she tried to manage the deceptions. “Hide in plain sight”. “Only deviate from the truth as far as is strictly necessary.” I was learning to see morality as an exercise in pragmatism rather than a set of strict commandments.

I could not see what she saw in this braying Ulsterman for whom she was just a bit on the side but it offered nothing to question her wisdom. I was a card in a house of cards and if one of us fell we all would.

I failed to realise her ambition for me until it was too late. She wanted me to leave home. This was my test. I had to move away from the comfort that I had been taking for granted. So, to please her, I went in search of a flat. This was the Eighties, I could afford it. And I was spurred on by the thought of the heated afternoons we would have there, drinking champagne and fucking.

It had to be central and I found a flat in Pimlico, ten minutes’ walk from the office.

On the day I moved in, she came to my office and demanded to know what I was going to cook for myself that evening. I hadn’t given it a moment’s thought. Food was what my mother always provided when we men got home from work.

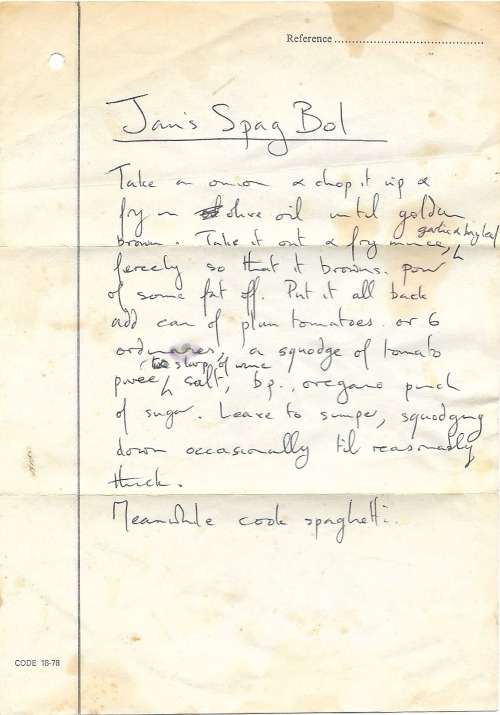

Seeing my bewilderment, she said, “Right, Schnucki, write this down.” And she dictated a recipe for spaghetti bolognese (I still have it. Any of you inclined to sneer at the inauthenticity might remember that this was the early 1980s. My Mum didn’t even use garlic, or basil. I make a modified version now.

).

On the way home to my new abode, I stopped off at Sainsbury’s and picked up everything on the list, then went home and dutifully made the thing. It was good. The next day she quizzed me on it and seemed content.

It was only much later that it dawned on me that this was the closing chapter of her project. Job done. She never visited me in that flat. We never made love again. In time, when I met the woman who was to become my wife and the mother of our children, we stopped seeing each other altogether. It hurt, yes it hurt. I felt as if I had been dropped from a great height Into an empty sea. I wondered what I had done wrong. My depression (a thing I had lived with since school but never understood until she had explained it to me) kicked in big time. My Pimlico flat of so much promise became a prison cell. It was only later that I saw the extent of the gift she had given me.

Reading it over, this all sounds a bit cynical and resentful. It isn’t. Can I just say that? The time I had with Jan, what she taught me, and more, so much more, what she saw in me and brought out of me, made a massive difference to how I lived and met the world from then on. It enabled me to find a partner and to father two children who still have the power to astonish me. I am still learning from it. It is no exaggeration to say that she rescued me and set me free and I will always be indebted to her.

The next to last time we met I said to her that I would always love her. And she paused then said “Yes, I think you will.”

And the last time we met, by chance, twenty years ago now, she as radiantly beautiful as ever, me now greying and a bit paunchy, she said, approvingly, like a master giving his dog an appreciative pat on the head, “You said you’d always love me.”

What was it the Jesuits said?

Actually, not pillows. I want to sound off about cushions. In essence, why do they exist and why did it suddenly become fashionable to strew them about everywhere, making it impossible to sit in a chair or on a sofa or lie on a bed?

I know, there have always been cushions. Well, maybe not always, but for a very long time. But until recently, their purpose has been to lend comfort to hard surfaces or support to resting bodies. They had, in short, utility. I am also aware that some cushions were made to serve another purpose, that of reflecting the taste or status of the owner, a purpose which was, at times, at odds with their primary purpose as their heavily embroidered motifs rendered them uncomfortable against the skin.

But that was little more than an aberration when compared with the present fixation which serves only to render furniture designed to accommodate human bodies unavailable to them.

You cannot enter a hotel bedroom these days without being confronted by rows of these smug, unyielding fabric balloons taking up the bed that you have paid to occupy. They seem to serve no purpose other than to frustrate your desire to lie down. So your first task is to shift them. But immediately that brings you face to face with the existential question, “where shall I put them?” Do you consign them to the floor, like banished dogs? Do you line them up against the wall, like prisoners before a firing squad? Do you cram them into the already inadequate wardrobe? Whichever course you opt for, you are aware that you are being put to unnecessary effort. You are now the slave to someone else’s conception of taste.

And for what purpose? They have no practical use and barely offer any ornament. They are just a self-indulgence by some “interior designer”.

But this awful embellishment has now crept, like a fungus, out of the hotel and into the houses of actual people. It has got so bad that what used to be a practical welcoming gesture “why don’t you sit comfortably on the sofa” calls for the response “because there is no room to do so”.

The alert host may note your predicament and offer a casual, “Oh just move those” – meaning those fat, encroaching cushions presently taking up every inch of the seat. And, once again, immediately, you are faced with a heightened version of the hotel bed scenario. Why should you have to? And where do you move them to? Which, itself, now contains the more delicate question: what level of consideration is owed to these bloated carcasses when clearly your host has gone to a significant amount of trouble to bring them into his or her home and fill every available piece of sitting accommodation with them. You cannot just toss them indifferently onto the floor as you might in the privacy of your rented suite.

So, like as not, you end up perched insecurely on the edge of the said sofa, your clenched thighs devoted to keeping a mere inch or two of your buttocks in place so that you don’t slide gracelessly to the floor.

Is this some kind of covert power play by your host? The living room equivalent of your boss offering you a low seat in front of his grand desk? Is it a subtle sign that you are there on sufferance; not in fact welcome and not to take your ease?

Or do the cushions reflect some deeper psychological affliction? Are they perhaps substitute children, as pet dogs and cats used to be? Larger and more intrusive cabbage dolls or flour babies? You cannot help but wonder where you stand in the pecking order of your host’s mind if a set of unyielding, micro-fibre-filled, fancy cotton bags take precedence over the obligation to give you somewhere to sit.

I imagine that this fad will eventually run its course, and I cannot wait for that day, but I do wonder what will replace it. Will the beanbag, that exquisitely uncomfortable toy of the middle classes in the seventies, make an unwelcome comeback? The time for its rehabilitation must be near. Everything else has gone to pot.

But I can assure you that if you come to my house you will find chairs and sofas that you can relax into and beds that offer you room to stretch your tired limbs. Life is hard enough. I intend to cushion the blow – without cushions.

When we arrived at the hotel bar, after a trying day, we were hoping for a bit of time to unwind and regroup before dinner. We had reckoned without the men, six of them, who had clearly already been there for some time. They had taken over the tables and high stools in the centre of the bar, were well down what may have been, but probably weren’t, their first pints of lager and were well into raucous mutually-affirming badinage.

We had first visited the bar, a part of what was supposed to be a four-star hotel in Taunton, on arrival a few hours before, after a particularly taxing day driving across England to, and the participating in, the funeral of an old friend and colleague. Then, it had only been the music in the bar that had been loud enough to be intrusive but, although it was still audible in the background it could not now compete with the level of sound emanating from this group.

We were booked to eat in the bar – the hotel had graciously allowed that my sister’s well-behaved dog, a nervous and still cowed rescue that couldn’t be shut up and left, could remain with her during the meal but not in the “dining room”. Fair enough, except that the dining room was in fact just an unpartitioned area of the bar. So in fact we had only the options of staying to eat or giving up our reservation in the hope of finding somewhere else that would admit us. And since we had, on arrival at the hotel, been required to provide a substantial deposit towards our evening meal, leaving, without the prospect of a serious argument, was not much of an option.

We had been joined by a friend from the funeral and had been anticipating a gentle conversation with him before going on the eat. Apart from us and the men there were only two other couples in the bar. Twenty minutes later, however, even though we were barely a metre apart, we were each already hoarse with th effort of making ourselves heard over the noise the men, now enthusiastically into a new round of beers, were making,

My only excuse for the interaction that followed, and not a great one, I acknowledge, when the time came for us to take our places for the meal, is that I was aware of how stressful the day had already been for my sister and had wanted this part of it to be as comfortable as possible. I therefore asked if the waitress could find us a table at a greater distance from those men. She looked around haplessly before confirming to us that we could only sit in the bar area “because of the dog”.

I did not react well, I accept this, but I reiterated that we would like to be further away from “those braying drunks”. The waitress, with commendable calm, replied that “they are not drunks. They are just a group of men who have come in aft the end of the working day.” I’m afraid her unwillingness to recognise the deleterious impact of the group riled me somewhat and I responded that if they were not drunk they were giving a good impression of being. She simply stood her ground insisting they were not drunks, just working men and that we had to be in the bar area with them because we had a dog. My reminding her that we were guest of the hotel and that the hotel had assured us when we booked that there would be no problem with accommodating the dog at the meal and that its vaunted mission was to make us comfortable was to no avail.

Fortunately, an hour, and several more beers, later, the men, amid noisy farewells, got down off their stools and left.

I dare say I can guess what some of you are thinking. I should have just got, and should now just get, “over it”, and myself. You will be thinking I was in a bar in a city centre. What did I expect? Why should I think it okay to want to spoil the enjoyment of some working men and why should I think it acceptable to confront a poor harassed waitress in the process? To that last part I put up my hand unequivocally. For as long as I can remember I have understood that, unless the person serving you is behaving obnoxiously from personal choice, you should never allow yourself the luxury of attacking or demeaning them.

I have seen it done so often: inadequate men and women, dress’t in a little brief authority, usually attributable to the overweening size of their bank balances and to the need to demonstrate what they are pleased to think of as their superiority, putting down those whose hapless misfortune is to have to attend to their requirements. Such behaviour is bullying, it is rude and it is indefensible. I am not advocating condescension, noblesse oblige, here. Don’t they know that there are only people in this world and that it is our human duty to treat every last one of them with the respect they deserve, even when you think you deserve better? I “don’t indulge” in such behaviour, or at least I shouldn’t.

All I can say, and my offered excuse rings hollow, believe me, is that my own challenging response was out of character and that it was triggered by a difficult day. And if I could have that time over, I hope I would behave better. But time only works in one direction for humans like us so I can’t go back and do better.

But perhaps, with that out of the way, now we could get back to the point. Those men.

I get that they had been working all day. But did that entitle them to make everyone else’s evening uncomfortable? I don’t think so. Don’t get me wrong. I am no saint, no temperance-driven killjoy. I too have been the worse for wear in bars. But, like it or not, and making due allowance for the reasonable desire to “have a good time”, I believe that nobody should be allowed to have that “good time” at the expense of other people.

It is, I think, a well-identified observation that the volume of noise produced by any group of drinkers rises to meet the level of the loudest member. That certainly is true of men (women, please do not feel left out, you have your own version of this behaviour). I have watched it time and again in the pubs I have visited. Sadly it is also the case that the loudest member of any drinking group tends to get louder the more alcohol he has consumed. Every joke has to be appreciated with a bigger outburst of braying laughter; every anecdote has to be topped by another increasingly inarticulate ramble delivered at full and yet fuller pitch. And so the braying ratchets up.

It is the unhappy lot of the licensee of the premises to exercise control over the behaviour of his customers (I’m not making that up; it is the law). Often a quiet word to the group will be enough to restore order, for the benefit of all and with very little impact on anyone’s fun. Indeed, having been in such groups on numerous occasions I can assure you that I have not been alone in welcoming such interventions. Better that, surely, than to wash one’s hands and allow the unbridled ravings of one man spoil the pleasure of the entire establishment until the whole situation is beyond recall.

Regrettably, some licensees would sooner take the soft option and let duty go hang. It is, of course, false economics because it will, in time, drive away good paying customers but they would rather temporise, kowtow to the drunken braggart, than confront him. It is not in fact limited to drunks in bars. We see the same subservience in other areas of our lives; profit put before people, entitlement raised over the common good, selfishness prized over consideration. Feudalism, which is still the bedrock of our society, always favours the bully. It has become “the British way”.

But it is not how it is supposed to be, nor how it has to be. One man’s, or indeed one group’s, pleasure does not have to be bought with the discomfort of everyone else and we should not be accepting of it. Just a little consideration and accommodation can enable us all to have a good time.

But until we learn that lesson, sadly we will all have to kneel so that some of us can bray.

Image courtesy of The Guardian

As Alan, Ron and I approached the door

Two Brimstone butterflies were brightly dancing.

So out of place. I thought was this a chance thing?

A common sight in meadow or on moor

But here in Basingstoke, at All Saints church?

A sight that made my tired and sad heart lurch

I tried to shed the possibility.

All that occurs has reason if you press

But superstition wants for something less.

I’d pitched my camp on rationality

Yet here’s my heart insisting it’s a sign,

These flitting yellow messengers divine

We’re taught to think of brimstone as God’s wrath,

His anger at the sin of unbelief,

But these two circling angels stemmed my grief

As they paid courtship on the old stone path

And, lifting off the sadness of the day,

They pricked my pompous gloom, blew it away.

Oh, Graham, you and I had walked so far

We’d strode the hills and glens, the moors and sands

I’d found redemption in your gentle hands

Then watched you dwindle like a dying star

I came today to say a last goodbye

And met instead the Brimstone butterfly.

Now in my mind you’re here again, not lost

On this March morning dancing in the sun

Insisting life’s not over, it’s begun

Just open up your heart and let it trust

I feel it now and hopefulness returns

My heart was stone but now a stone that burns.

RIP Graham Osborne, a Good Man.

Iain M Spardagus, 26 March 2024

It was just a door, when it appeared in my head as I lay half asleep.

Just a door, a plain wooden door, unpainted, half glazed, at the end of a short, whitewashed passage just wide enough to contain it and hung with deep shadows where the daylight streaming in through the glass could not reach.

I must have been ten feet or so away from the door. Through the glass I could make out The promise of a summer garden, lawn and mature shrubs, and I had a sense that out there was bathed in hot sun.

Just a door, yet it seemed in my head as I stood before it that there was a whole house behind and around me. I could feel its weight and that there was a time and a place in which it, and I, belonged. Somehow I knew that the time was, and the house was, and the door was, and I was, back sixty to seventy years ago. I searched for some clue to how I knew this but there was nothing. It just was.

Was I trying to return to some golden age? I thought I knew better than to believe in such a fiction. And yet this door seemed to promise that reassuring certainty that I last felt all those years ago when I was just a boy and trusted that the adults around me knew what they were doing and had created the stable and benign environment which, for all I knew, was all there was. Just a door and yet I knew that if I could, and did, approach it and turned the big dark brown round knob on its right-hand side I could walk out into that garden and still feel safe. Unthreatened.

I wasn’t going to do that. For all the time that the door was there in my head, we were unmoving; the scene and the distance between us remained fixed, totally, comfortably still. Only inside my head was there churning, as I tried to pull back details of the house to which this door belonged, wondering if I knew it, knew its spaces and smells and the way the light fell on its surfaces, the way the dust danced in the sunbeams. But I didn’t and I realised that the mere effort to recall was causing the door and the passageway and the fragment of the garden that I could see through the glass to lose definition. I did not want to lose it yet.

Just a door but to me it seemed to hold a significance, the assurance of a quiet sanctuary that I had never known but had always wanted and now needed more than ever. It stood somehow as promise and protector. It stood where I wanted to be.

And then it faded and was gone. And I was left with its memory. Just the trace of a door yet my mind insists it was so much more than that.

Caesar’s Lament

A poem for the Ides of March:

I asked the guard “How fares the day?”

He answered me “Hail, Caesar.”

I should have known right there to stay

In bed, not play crowd-pleaser.

My hearing isn’t all it was,

So my soothsayer’s warning

“Beware the Ides of March” I tossed

Aside as idle fawning.

I thought he said “the icy blast”

So wrapped my toga round me

And headed for the Senate fast

Where dear old Brutus found me

But Brutus stuck me with his knife

He said it was his duty

Else I’d be emperor for life

I gasped, “I’ll g-et you, Brut-e”

Then others joined in the attack

I felt these stabbing pains

They went for me front, side and back

Now I’m Roman remains.

There is no excuse for threats of violence, still less actual violence, against anyone, even our MPs. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t reasons.

Those who would seek to govern us would do well to look into our history. I mean deep into it, back to the origins of our judicial system, and back to the lives of those who were our feudal overlords.

Those feudal overlords first, from a time well before the arrival of that most famous illegal immigrant and boat person, William “the Conqueror”, from whom most of our aristocratic families seek to derive an entirely spurious credibility for their generations of exploitative privilege. These bullies settled most of their differences by fighting, or assassination or both. Sometimes, a lot of the time in fact, the fighting involved co-opting our forebears, the peasantry in other words, people who had no actual skin in the game but were simply in hock, one way or another, to their masters, to beat the living daylights out of each other or die, often both. These rumbles were known as “wars” or “battles”, provided they were sanctioned by the gentry.

But when you train a dog to fight you can’t claim to be surprised when he does. And sometimes the peasantry lost its sense of place and started fighting for itself. To these unsanctioned skirmishes was giving the word riot.

The kings of old could see the dangers inherent in allowing the general populace to go around beating each other up or threatening their betters every time they felt aggrieved. It wasn’t that they cared much for the peasants themselves. It was more that vendetta and vengence and unresolved discontent undermined their authority and promoted lawlessness (two sides of a significant coin).

As the police have long understood, when a bar brawl is underway, the safest thing to do is to wait outside until the worst is over. But mayhem was bad for the “King” business, not just because it reduced the numbers of available, fit, workhorses. You cannot tax a population that does not recognise your power over them and you cannot rely on them to turn out for you if they don’t think you have their interests at heart. It doesn’t matter whether you are a phoney. It only matters that they don’t think so.

And that, children, was the origin of the rule of law. The old kings, with a wisdom not widely put to work, set themselves up as “the fount of justice”. They, the state, as we would now see it, saw the imperative and the value of their being where people turned when they had a grievance, an independent and impartial arbiter between individuals.

And the idea sprang from that that no-one was above the law (except the King, of course, who was only “answerable to God”). The law was to apply equally to all (except him) and was to be available to all.

It worked, by and large. Civil disputants had a place to go and everyone accepted that the policing of the law was the King’s business. And, through this patriarchal intervention, over time civilisation flourished.

Fast forward to today. The past forty years, in particular, have seen a lot of forgetting. Money has a stench that has the capacity to overpower the sense of smell needed to identify corruption, and the generation of a class of super-rich who both have, and want, no responsibility for actually looking after the nation, beyond being free to despoil it in the interests of their own increased wealth, has led to a gradual but by now significant backing away from the notion that people, the generality of people, should have access to the law. If you close your eyes to what history is trying to tell you, you can see their point. Keeping a justice system going for rich and poor alike, making it a fundamental tenet of civilisation that the law applies equally and must be administered without let or favour, is an expensive business. And it cannot be guaranteed to ensure that the people who think they are in charge will win.

The trouble is that when you start undermining access to justice you recreate that very vacuum that will get filled with people taking “the law” into their own hands.

I am not here to argue that the period since the courts and access to justice were established has been a time of unqualified peace and law-abiding. There are many examples in the intervening time of riots and revolts, often very bloody. But I would suggest that an objective eye looking into any of these would find the same root cause: a sense among those involved that they are not being listened to, a sense that they have no available alternative. There is, inherent in all people, however simplistically, a sense of fairness, and of unfairness – injustice. The judicial process, to be effective, should buy into that sense.

This is not to suggest that the law should capitulate to the mob. Ideally it should never come to that. But the presence of a system of justice in our lives, the held belief by the majority of us that there is an alternative to resolution by violence and civil disobedience, should militate against our allowing the headstrong and the vociferous to be our guide.

It is not just about the effectiveness of a judicial system, of course. Once you establish the idea that a nation is a liberal democracy you again give form to the belief in people’s heads that the state should work for them. But ideas like that, once instilled, are hard to shift and when it becomes inexpedient to the ruling class, or to those who believe that they are the ruling class, notwithstanding their predecessors’ accession to the idea that the power belongs to the people, to listen to those people and to their grievances, when the ruling class decides that anyone who does not reflect their self-serving grasp of the nation’s well-being as synonymous with their own unchallenged advancement, is an “activist”, a “terrorist”, a “subversive”, someone to be put down, rather than debated with, then again the board is set for anarchy and anarchy begets violence and violence disrupts everything, even the generation of wealth.

In short, it behoves our would-be tyrants, the Goves, and their ilk, to heed history and, so far from introducing draconian measures to crush what they see as the impertinence of dissent, to pay it due respect. It may dent their profits in the short term to have to cede a little ground to the concerns of ordinary people but in the longer term it will shore up the stability from which real wealth and real progress stem.

It was, I believe, a Persian general, a long time ago, who said that when you have your enemy on the run it is vital to leave them somewhere to run to. A cornered enemy has every incentive to fight to the death.

And it was, I believe, in V for Vendetta, that powerful polemic on the freedom to dissent, that the thought was voiced “The people should not be afraid of their government, The government should be afraid of its people.”

But I would like to put it another way: a government that wants its people to listen to it should first cultivate the habit of listening to them.

Or as Stephen Covey once expressed it: “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.” Making a practice of listening to others, especially the ones with whom you do not think you agree, is almost always disarming for them. And sometimes you learn better.

Lessons that the ignorant wannabe authoritarians presently in charge of us would do well to learn before they return this fine country to an ungovernable and violent past.

In honour of Amal Alamuddin Clooney on International Women’s Day 2024

She was an international woman

As she queued to get on board

A rage in her consuming

She wouldn’t be ignored

She was an international woman

And this would be her day

Men had always had it coming

Now she’d make the buggers pay

She was an international woman

Lady Justice with a sword

Misogyny left her fuming

She didn’t want to be pawed

She was an international woman

Not just some rich man’s bawd

In her heart her power was blooming

No more just a broad abroad

Gillian and I were enjoying a very pleasant pre-prandial drink at the Craigellachie Lodge (a delightful private hotel run brilliantly by Scott and Jodie and their wonderful team. Go there) when it happened.

At first it was just an overheard altercation. It had been raining. Not the cold, sticky rain of the south of England that makes you want to take a shower to clean yourself but the soft, gentle rain of the Highlands. We heard the front door slam and then a loud and peremptory Bronx voice moving away into the depths of the house, “I’ll need towels in my room”. Followed by the gentle responding voice of Sam, the Lodge’s hard-working maid of all works, “I’ve put fresh towels in your room.” Then, right back at her, that hard Bronx again, “I’ve used them. I need more.”

No please or thank you, note, but then experience tells me that you can’t expect manners or respect from the average US citizen. Brought up to believe that they are anybody’s superior, they don’t do politeness, presumably equating it with an unpardonable subservience. Just look how they behaved at that tea party.

A while later the Bronx voice arrived with its owner in the bar to bray to the same Sam, “I’ve been to Macallan’s today to examine my cask. I’m told Glenallachie’s good. Which one do I wanna drink?” Then he sat down about ten feet away from us and, without invitation, started telling us about his life.

Now, in contrast to what I have said two paragraphs up, most of my encounters with Americans abroad (that is, outside the US) have been good. Republican thugs are usually too locked in to their narrow, ignorant sense of their inexhaustable self-worth to travel the world. They don’t tend to have passports, thinking no good can exist outside of God’s Own Country, and those that do, and use them, tend to stay in air-conditioned concrete and glass facsimiles of their home grown lack of imagination and not in bijou hotels older than their regrettable take on civilisation. The ones you tend to encounter in the backwaters tend to be gentle Democrats. So, and I think I speak for Gillian as well as for myself, when it came to welcoming this intruder into our conversation, despite what we had overheard, which could have been down to human pique at the weather, we were initially prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Within five minutes we had learned that this man had only arrived here yesterday, having given up the company of his friends, who had been engaging in manly pursuits in Germany, compelled as he suddenly was to visit “Scat-land” (to, as he rehearsed for us, visit his cask at Macallan’s, this clearly being a point of great significance to him that perfect strangers should know about him) but that he would be leaving tomorrow because he wanted to see Edin-berg before travelling back the next day to his family in Los Angeles because he was an Orthodox Jew and family was where he must be every week from Friday night through Sunday without fail. He had told us in passing that, as he raced through the airport to catch his plane to Scat-land, he had dived into the Chanel store and demanded that they provide him this instant with the latest Chanel handbag because his wife loves Chanel handbags and had to have the latest. He had six minutes to board so they’d better produce the one bag and sell it to him. He segued into asking us whether he would be able to view the Cassle (Edinburgh Castle) from his suite in the Bal Morall (which he pronounced as if it were two words that rhymed with the OK Corral). It took a moment to realise that he was referring to the prestigious and frighteningly expensive Balmoral Hotel. Though these mis-steps in pronunciation were in themselves forgivable they issued from his mouth so arrogantly that it sounded like cultural imperialism, so forgive me the somewhat snide tone to my recollection. Anyway, while he briefly paused for breath, we were able to inform him that that was the hotel in which J K Rowling holed up to finish the last of the Harry Potter books, at which informational nugget he contrived to look both puzzled and pleased.

But he was just warming to his thesis. Next he told us that he came from a wealthy New York Jewish family but he had walked away from them to start up his own sports equipment business which was very successful (of course); and that “nobody” could live in New York any more. Then, before we could ask him to elaborate, came the big reveal. He couldn’t bear to fly on the US internal air flights any more “because they are all full of Blacks and Hispanics.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Gillian flinch as I too took on board, much too slowly, what I had just heard and how casually it had been expressed, with a confidence that anticipated understanding and acceptance. There was no apology in it; no trace of hesitancy or uncertainty. Certainly, no hint of irony. Then, in case we hadn’t fully taken in what he had said, he doubled down without prompting. “Yeah, European airlines are so much better than the US ones which are all full of Blacks and Hispanics.” No mere slip of the tongue, then.

Now, I should say that I am an atheist and, though of a skin colour known as “white”, I am a committed believer in the proposition that no racial group in this world has any claim to superiority over any other. That cuts both ways, of course. It means that I must, and do, accept that none of us is inherently inferior, regardless of our racial background or the level of pigmentation we have been allotted. These aspects of my awareness, the atheism and the belief in fundamental equality, compel me to reject any pretensions of supremacy by the representative of any nation or religion. There are NO chosen people and there are NO chosen religions. There are just people.

But it also means that I must accept that there are examples of goodness, and badness, in all of us. I really should not expect any individual, regardless of his race, religion or culture, to be immune to bigotry.

Having said that, however, Judaism has been at the heart of intellectual, psychological and emotional intelligence and human progress for centuries so I still I found myself fazed by the unexpectedness of an articulate Orthodox Jew and self-confessed family man comfortably giving voice to an indefensible racist attitude. How could a member of the most oppressed and persecuted tribe in all history be so unaware of the imperative that came with it to stand with other oppressed and persecuted groups? How could he have become so depraved in his thinking as to believe, let alone express to total strangers, that two other down-trodden and unjustly maligned clusters of people merited such a sneering put-down?

His subsequent pronouncements gave the clue. He was a Republican and a Trump supporter. Which changed the question only marginally. How could a thinking, morally driven, successful, family orientated man associate himself with a loser and amoral crook?

The answer, sadly, probably lies with a rather desperate need to belong; the same need that draws inadequate individuals into gangs of bullies the world over. Better to be the predator than the predated upon, better to be the oppressor than the oppressed. Better to deny the powerful strictures of your faith and the lessons of its history than to side with those whose egregious treatment, like that of your ancestors, cries out for fairness, decency and mercy.

It is a paradox but a very common one. In this country, the UK, we see one-nation Tories, people brought up with the patriarchal belief that it is their responsibility to serve the nation’s interests to the best of their ability even to their own detriment, kow-towing shamefully to shysters, robbers and rogues simply in order to maintain their positions of privilege over the common herd. We see working class men and women manipulated into vociferously espousing the whipped-up hatred against those worse off than themselves, a hatred that has been sold to them by scurrilous, exploitative spivs, rather than question the depredations to which they have been subjected by those same charlatans. We see it start in the school playground and drill its roots into our children’s psyches so as to become second nature and make them easy prey for the debauched. We see it confirmed in our working relationships where faux-loyalty to the boss so as to keep our jobs and “get on” enables the perpetuation of abuse of our colleagues. We see it hammered home in our newspapers telling us that those who take a stand against injustice and tyranny are the “enemies of the people”. That to be perceived as “other” is to make yourself a legitimate target.

We need to excise it. We cannot go on with this poison in our hearts. But we are all susceptible, even those whose ancestry and experience should have taught them to know better.

I fear I may never return to the Oxford. The last time I was there I was in mostly delightful company - my son, my daughter’s boyfriend, our dear friend Gillian, who had first led me, a long time Rebus fan, to the place, and two young friends of Gillian, who shall remain undeservedly nameless – these last two had spent the day rather tediously acting as silly hipsters (I am sure it wasn’t at all tedious for them but I can assure you it was grating on us).

I sat everyone down in the back room, gathered the order for drinks and proceeded to the bar. Like an over-eager puppy, the male “hipster” decided to follow me. From his pointy brown brogues to his over-coiffed hair, he was the embodiment of twat to anyone looking at him, but in his own mind, clearly, he still had his point to prove. As I ordered his Guinness he seized the moment to demonstrate the point.

“Make sure you let it stand before you top it up, won’t you.” Fired like a precisely targeted jet of ice-cold water, a sentence that could be used to by the compilers of dictionaries to exemplify “peremptory”. And spoken in clipped English, all the more exasperating because he has impeccable Geordie credentials.

The young woman serving me paused. She had dramatic timing that Maggie Smith, if she had been there, would have admired. Slowly, menacingly slowly, she turned her head in our direction. “Thank you. I have poured one of these before.” Ice water had been met by Edinburgh frost and frost had won.

There were murmurs at the bar. One did not need the sensitivity of a seismometer to read their mood. My hipster friend turned on his worn-down heels and, in the best traditions of the officer class to which he aspired, left me to dig myself out of the hole.

I thought, I swear I did, in that instant, of the wonderful Miss Toner from Tutti Frutti, outraged by her boss’s behaviour, announcing to a railway carriage full of embarrassed passengers, “I’m no wi’ him, he’s wi’me”. But sadly I do not have her balls.

A grunt from Rebus would have set things straight, or at least let the locals know that he did not give a toss about the lot of them. But I am not a fictional detective of legendary drinking ability and practised terseness.

No, I am just a frightened old man, still desperately trying to live up to his mother’s ideal of gentlemanliness – offend no-one. And everyone seemed to know it. I did what I could, pulling a face that I feared even Steve Martin, not a man known for facial subtlety, would have baulked at and mumbled “Sorry about that”. Tumbleweed appeared in the bar and rolled noiselessly down its length. I paid in silence, thought of asking for a tray, decided against, tried a confident “Thank you” which, as mounting anxiety had clasped its fingers around my throat, came out as a strangled “thingyer” picked up my drinks and, trying not so much to muster some dignity as just – not – trip – up – the – steps – please, left the bar for the back room. As I did so, I heard conversation start up again.

I bloody hate hipsters.

A traditional folk song from twenty minutes ago.

As I walked beside the Fiddich

On a driech November day

I came upon a water sprite

A-barring of my way

I said to her why stop you me

I’ve nothing you to pay

But she only smiled a secret smile

And this I heard her say.

“They’re draining down my waters

Here and the River Spey

To make some awful whisky

That keeps men drunk all day

It’s not enough they brew it

To keep the cold away

They do it for the money

And it’s me that has to pay

Glenfiddich never was much cop

Macallan used to be

The Smiths’ Glenlivet’s gone to pot

And who needs Glen Moray?

I don’t begrudge Balvenie

Glen Grant or Allechie

They use my waters to the good

And me respectfully

So take this as your telling

And take it here from me

If men abuse my waters

I’ll not stand idly

Don’t drink the shoddy product

Of the whisky factory

But stick with the distillers

Who make Uisge faithfully

Back in the 50s, my family drove through the rural backwaters of Middlesex in our Old Ford Anglia (the model before the one with racy styling that Harry Potter trashed, built like a set of boxes on wheels. The sort of thing Childe Boris might have constructed out of cornflake packets and painted as black as his heart). We were headed to the village (you heard me) of Kenton to visit my surviving Great Uncle and his two sisters.

The sisters were “maiden aunts”. I should explain for the younger audience that a “maiden aunt” was, in those days, an aunt who had the good sense to avoid, or lacked the qualities needed to attract, a husband. I don’t know if there was an actual equivalent descriptor for an uncle who had had similar good fortune, but there were numerous examples of brothers and sisters living out their lives in platonic mutuality. This was before social media and any aspersions cast upon such people were left to village gossips.

But I digress. The point I was headed for when I rudely interrupted myself was that, of the two ageing ladies, one was known as “the nice Miss Colbert”. And the reason she was thus known was because she wasn’t always unpleasant to people.

What a great accolade! To be regarded as nice simply because from time to time you curbed your waspish proclivities. Even as a child, hearing my usually reticent Dad (he would have said “diplomatic” or “discreet”; he was a lifelong civil servant) describe her thus, I felt that this was not something to take pride in. My Mum’s take on “good manners” was “never offending other people” (which I also came to question in time. Some people are so offensive that you cannot help offending them. Just be nice about it!).

But that is just the background to my point, which I will now attempt to make.

James Cleverly, probably the most inappropriately named member of the present government now that Chris Pincher has left, has acquired a reputation for being – yes an idiot – but a benign idiot. But hearing him acting up to the populist draw of his recent appointment as Home Secretary (which, let’s face it, had more to do with making room for that pink-faced PR liability, Cameron than with any ministerial merit on Mr Cleverly’s part), I can’t help drawing comparisons with the “nice” Miss Colbert.

In short, do we only think of him as the “nice” Mr Cleverly because he is not always a viscous Tory arsehole? Looking at his most recent positional takes, I am beginning to think that we do.

I accept that, unlike my maiden aunt, Mr Cleverly has the excuse that despite, or possibly because of, his legendary stupidity, he retains an astonishing ambition, not merely to remain a member of the gross insult to the Conservative Party that the nasty racist rabble current holding the party to ransom have made of it, but to lead it. Why is beyond me to reason. I could better understand the egregious Matt Hancock’s desire to participate in “I’m a Celebrity”. Maybe he is short of the readies but frankly prostitution, or writing for the Guardian, would be a more honourable way of filling his bank account if so.

But I find it hard to believe that James Cleverly is happy with the level of unprincipled wickedness he is espousing. He’s got the job, he doesn’t have to try to outdo his two morally repugnant predecessors.

You don’t have to be left wing to see that the Rwanda concentration camp model that the Home Office has been wedded to under Braverman and Patel as a “solution” to the refugee crisis is utterly devoid of merit even as a bit of electoral PR. The figures alone do not add up (one jumbo jet’s load of refugees for £400 millions: £1.8 millions per refugee, according to the NAO). And the want of humanity is staggering.

And now he is limbering up to place further curbs on political protest. “Political protest” is, of course, a tautology. All protest, other perhaps than a child’s protest at having to eat up all his greens, is political. Politics, as my old constitutional law lecturer tried to drum into us, is about power. Protest happens because the people with the power are not listening to the people without it. It may not be textbook democratic, but, pitched against that standard, it beats the office of Home Secretary hands down. Or any of the other ministerial and sub-ministerial unelected appointments, for that matter.

The present Administration of All the Shysters has made catastrophically damaging inroads into our age-old right to protest and done so on the most specious of grounds, threat to national security, for which there is no, repeat, no, evidence. Their true motivation is to control the message – in other words, to exercise a monopolistic command over what we hear each other saying - which, let’s face it, is all they have. But, and I wish there was a less dramatic word I could use here, that is a core fascistic ambition. Straight from the playbook of the worst examples of tyrannous depravity.

It is no use trying to persuade us that if we don’t like our government our answer is through the ballot box. This is not a democratic nation. The main parties have, across the centuries, made sure of that. And even if the electoral system did enable the making of free and informed choices, which it does not, once in four or five years is just not good enough. As we have seen with “austerity” and brexit and the environment and the economy and public services, a lot of lasting damage can be done in four years. A government is not just for Christmas. It is supposed to act in the best interests of the nation, and be accountable to the nation, at all times. Protest is a part of that. A legitimate part of it.

So, back to the “nice” Mr Cleverly. What we are getting from him just now is not at all nice. It is, in fact, authoritarian, manipulative and downright shameful: anti-British, if you like. Is that who he is, or just how he thinks he has to pretend to be? And if it is the latter, can he just think it out again, please? I really don’t think he is a bad man, but it would be “nice” if he didn’t think he has to be.