The blog of Iain M Spardagus

Freedom of mind and freedom of expression are the bedrock of human society.

The probability is that you will never read this. Nobody reads what I write here, so far as I can tell. In a way that’s what makes it safe. But if you do read this, you probably won’t reply, and, sad as that makes me feel, that’s okay. You must have so many people trying to claim your attention.

I just really want to say “Thank you”. Thank you for kick-starting my heart back then in the 70s. Though, like a vintage car, it is in constant need of stripping down and refurbishing (my heart, that is) I don’t think it would even have turned over if it wasn’t for Stars, and then Between the Lines.

I am 72 now, and that means, like it or not, I am running out of time, but I still play those early albums. In fact I am sitting out in the garden now and annoying the neighbours with you (I don’t care).

But you seemed true then and you seem true now. The only time I really feel at peace with myself is when I am hearing you reminding me how to feel. Leonard Cohen could do it sometimes but you, you hit the spot. Time and time again. Not with what we had experienced in common but with what I knew it would be like if I ever did. And you still do it.

I sometimes wonder how you survived. I wonder how I did. But we did. We have.

I raise my glass to you. While I still have the strength. All wishes done. Just this.

Thank you.

Iain

To the tune of “Joanna” by Jackie Trent and Tony Hatch:

Rwanda

I can’t believe they’re sticking with Rwanda

It’s leakier than a kitchen sieve

Rwanda

With millions of our money thrown away

It’s foolish, it’s inhumane and positively ghoulish

They’re clinging to a policy so mulish

The more they’re told it can’t succeed

The less they heed.

Rwanda

They know it’s just some empty propaganda

They’d have more chance of mating with a panda

And yet they’re still pretending it’s the prize

A jumbo of refugees will never stem the tide

It’s sense defied

Rwanda

Rwanda

It’s time to pull the plug on Tory lies.

A jumbo of refugees will never stem the tide

It’s sense denied

Rwanda

Rwanda

It’s time to pull the plug on Tory lies.

He woke suddenly to the sound of barking. The damned neighbour’s damned dog again. There was no light coming through the gaps between the blinds. He reached out for his phone and picked it up. Immediately the screen burst into life, telling him it was 05.15. He groaned and put it back down. The alarm would go off at 6.30. Between now and then there was little prospect that he would get back to sleep. Again.

Inside his head there was a tiny, jangling, fragmentary image of walking down a road. It must be the remnant of a dream but he could remember nothing more of it and it was fading even as he came to.

He realised that he needed to pee. This, too, was becoming a nightly occurrence. He had clearly reached “that time of life”. The thought did not please him but the future held only more of this: more decrepitude, more nagging awareness of limitations in a body he used to be able to treat with the indifference of youth.

Switching on the bedside lamp, he threw back the duvet in a gesture that reflected his disgruntlement and turned his feet to the floor, rising stiffly before tottering to the bathroom. The stream was fitful and did no justice to the urge that had prompted it.

Returning to the bedroom he decided to straighten the duvet before getting back into bed. But as he went to do so, he noticed a scattering of black dirt at the foot. He had had to brush some muck off when he made the bed before but this seemed more noticeable. He wondered where it was coming from. Puzzled, he sat down and lifted his right foot as far as it would now go and angled the sole towards him. It, too, was black with grime. Where from? He had showered yesterday and had not, to his knowledge, ventured outside since then without his shoes. Martha’s chiding him over the years of their marriage had long since put a stop to that kind of behaviour. “You’re walking dirt all over the house. Put something on your feet when you go out. And leave them at the door when you come back in. I haven’t time…”

He lowered his right foot, aware of the twinge in his knee as he did so, then carefully raised his left foot. The sole and heel were again black with dirt, just like the right.

By this time, baffled as he was, he was too far awake to think of getting any more sleep so he decided to go downstairs and make himself a cup of tea. “May as well get the day started,” he heard himself say out loud. He found himself doing this more and more now that he lived alone.

On the stairs was more of the black dirt. “I’ll attend to you later,” he growled. This was not a good start to the day.

After his first cup, taken with the now obligatory army of pills, he showered, taking care to wash his feet thoroughly, then dressed and set about cleaning the stairs and changing the sheet on the bed. He hardly noticed how tired he felt but spent a good hour in the afternoon dozing in his armchair. The rest of the day passed without incident and, soon after supper in front of another tedious reality TV show hosted by some gurning, toothy, fake-tanned fool camping it up for the camera, he locked and bolted the front door, dropped the keys into the bowl on the telephone table, turned out the lights and took himself irritably off to bed.

He woke in the middle of the night with the awareness that his pyjamas were wet. Then he realised that his hair too was wet and that the pillow and sheets under him were also uncomfortably damp. Had he been feverish in his sleep? He had had night sweats before. And he did feel rather chilled. But maybe that was just the wet cotton clinging to him. He swung himself upright on the edge of his bed and pushed himself to his feet. That wretched dog was howling, probably wanting to be let in. The sound of it drew him to the window and, pulling one of the blinds aside, he saw that it was raining steadily.

Again, the sudden realisation that he needed to pee. He turned away from the window and went to answer the call. When he returned from the bathroom he went over to the chest of drawers and pulled out a fresh pair of pyjamas. He changed and then, exhausted by the effort, flopped down on the bed and was, within minutes, asleep again.

The alarm woke him. Last night’s wet pyjamas were still on the floor where he had left them and he picked them up, wondering again how they had come to be soaked. He remembered the rain in the night but could not find any mental association between it and the state in which he had wakened earlier. Then, at the edge of his mind, that dream about being in a road flickered. It wasn’t much of a memory: in his head the scene was dark and the fragment of road, a tar-black narrow street of indistinct houses, glistened before him in silence. That was it. He shook his head and it cleared.

He tottered towards the bedroom door, head down, concentrating on staying upright as he manoeuvred around the end of the bed and on not catching his little toe on the unforgiving leg which had caught him out painfully before. This was how he came to see the shadow of a shape on the carpet, a faint footprint facing towards him, mapped out in traces of mud. Then another behind it. He opened the door, momentarily fascinated by this reverse trail, and followed it back to the top of the stairs. Looking down he could make out more of then, one on each tread each one slightly more definite than the last as they disappeared into the gloom of the hall below.

When he had showered and dressed, scrubbing more grime off the soles of his feet, he attended to the trail of footprints. They were harder to make out on the tiled hall floor but he traced them back to the front door. And all the while he was trying, and not trying, to make sense of what they were telling him. He had no belief in the existence of ghosts and was not about to be persuaded by a few marks on a carpet but they did seem to point to a visitation of some kind. He checked the door. The bolts, top and bottom, and the chain were still in place as he had set them the previous night. The mortise was still turned. No-one could have entered the house through that door last night.

Making himself a slice of toast he sat himself down in front of his PC and brought it to life, entering his password, with painful deliberation, one index finger at a time. When the screen opened, it told him that he had new notifications waiting for him from his doorcam. After an initial fascination with these messages when his son had first installed the camera and the software, he had since grown bored with grainy images of cats passing before it and the occasional visitations from bulbous-faced leaflet droppers and rarely bothered to check them any more. But now, when he opened the app his agitation quickly reached levels of alarm.

Opening the most recent first, he saw his bedraggled self approach the door. Around him was a false grey representation of darkness. His hair was plastered to his head and droplets of water were falling from his chin, nose and ear lobes. But the expression was blank, unseeing and unreadable. The time recorded on the screen was 03.13, just seven hours ago.

After a few moments while the shock ran through him, he moved back to the next most recent clip, The movement of the camera indicated that the front door had opened then his pyjama’d figure passed in front of it, leaving and walking down the path into darkness. But this time the meagre light was different, sparkling, because, he realised, it was being defused by rain falling and catching the glow from the porch lamp. The time on this clip was 02.46, the date today.

The next clip, like the first he had viewed, showed his return to the house. No wetness this time but his sparse hair was wind-blown. As he reached the door, the camera caught his expression, again glazed and unaware. He let himself in without any apparent fuss and the door closed.

He clicked on the next one back and in the distorted greys of infra-red capture was the back of a figure he did not doubt was himself, clad only in pyjamas, passing in front of the camera then down the front path. The steps were dogged, plodding, unwavering. The shoulders were stooped. The head looked neither right nor left, as if not to be distracted from its mission.

He looked at the date and time of the clip. It was from the day before, at 04.24am.

He looked at four more. The same sequence presented itself on each of the previous two days. Before that, nothing of the kind, just random recordings.

He slumped back in his chair, trying to take in what he had just seen. Though he had no personal recollection of it, the evidence before him was compelling. And it fitted now with what he had woken into, the soiled carpet and bed, the wet pyjamas. He had gone out in the night. Four nights running. Was it possible? Could he have been sleepwalking? He Googled sleepwalking. So far from dispelling the possibility it only served to confirm to him that he could indeed have been doing so.

The thought niggled away at him. He tried to recall whether at any other time in his long life he had done anything of the kind. A vague memory from childhood briefly came to him but vanished as quickly when he tried to give it shape.

But today was his weekly shopping day. He didn’t venture out much these days since Martha had passed, limiting himself to the half mile trek to the local Spar which carried everything he wanted and could afford. Even that had now become an effort of will as it involved walking through the underpass where she had been found, face down on the filthy ground, her head scarf awry, her knees and cheek grazed, and her handbag gone. The handbag turned up half a mile away in some lock-up garages, strap snapped, purse missing of course. Not that there would have been much to steal, even though she had been on her way back from collecting their pathetic State pensions.

He was aware that, in all likelihood, his journey would require him to pass those young louts who hung around the estate in their dirty hoodies and trackies and their stupid, clumsy trainers all day. Malevolent clowns they looked like. But if he could just keep his head down they might just settle for a bit of verbal abuse. He knew, though, that he wouldn’t be able to let the confrontation pass without showing his contempt for them and in his mind he could see that leading to his being jostled and even spat at, and even the thought made his heart start pounding painfully in his chest.

Why he couldn’t let it pass he couldn’t honestly say but he knew that this visceral hatred had started before Martha’s “accident”, as the police had insisted on recording it (heart attack, nothing to investigate, they’d insisted, though he was sure that scum had had a hand in it). Those worthless yobs, their livid daubs had defaced the subway within days of its opening and they hung around it like trolls around a bridge harassing any decent folk who just wanted to go about their business. Young thugs, the lot of them. Needed locking up, or a spell in the Army. Teach’em some respect.

But he wasn’t going to let them defeat him. So, at 10.30 he swapped his slippers for his brogues, tied his tie before the hall mirror and wrapped a scarf around his neck before hauling on his overcoat and buttoning it up. He picked up the canvass shopping bag and stepped out of his front door. His eye caught the tiny shining lens of the camera as he double-locked and checked the door before turning down the path and through the gate and this brought back to mind those images he had found on the PC.

He was so wrapped up in thinking about what he had seen that he arrived at the subway before he knew it. There were two of them there, lounging on the wall where the path turned down, hoods over their heads, the peaks of their stupid baseball caps poking out from them almost obscuring their pale, weaselly faces. Two bikes were strewn carelessly across the footpath. He gritted his teeth determined not to give them any cause.

Still, as he passed them, he could not stop himself raising his head and glowering at them. One of them just looked down. The other sniggered and muttered something.

He passed on into the dark opening of the subway and suddenly it struck him. It was here, he could hear himself thinking, here she died, and he imagined her frail old body lying there all alone, helpless, and he felt every muscle clenching along with the thought. His chest tightened. But he was damned if he was going to show weakness in front of those two louts. Just keep moving.

Then, without warning, his left knee buckled and he felt himself lurch sideways, his hand making contact with the cold, greasy tarmac as he tried to stop himself collapsing. A second later he felt a hand on his attempting to lift him and he heard a thin young voice, “Y’all right, Grampa? Watch yourself, now.”

He could not help himself. Angrily shaking off the hand he roared, “Not your Grampa. Get off me. Fuck off!” Even in his confusion, the vehemence of his outburst surprised him.

Not just him. Instantly the boy jumped back, “Okay y‘old git. Just trying to help. Piss off then.” And turned and walked away.

He hauled himself to his feet, brushed some black greasy dirt off his knees and hands. It reminded him of something. But he shook his head and stumbled uncertainly on his way.

On his way home, still shaken, the sagging canvas bag, now weighed down with a few meagre supplies, hanging from one hand and banging against his leg, he decided not to use the subway. It took him a fair way out of his way but he made it back to his house, out of breath and aching but relieved. He hung up his coat and scarf, wrenched off his tie and unbuttoned his collar, then put the food away in the fridge, made a cup of tea, changed back into his slippers and slumped down into his armchair. When he woke the tea was untouched beside him and stone cold. And he still felt unsettled.

As he was locking the front door that evening he decided not to put the keys in the usual dish. He was determined not to have any more nocturnal adventures. Walking into the kitchen, he looked around then put the bunch into the bread bin, closing the lid. Then he climbed the stairs wearily, grateful that another day was over.

His eyes opened into the darkness that resolved itself into the shadows of his room. The total silence was almost physical and unusual. His phone told him it was 04.02. Then his bladder demanded his attention and he heaved himself up out of bed. He didn’t bother with any lights at first. He had done this so often. After he had peed he shuffled across to the basin to wash his hands. His eyes had adjusted now to the minimal light coming through the bathroom window and as he stared into his shadowy image in the mirror he was aware of what looked like blotches of inexplicable darkness. His hand found the cord for the vanity light and he blinked painfully as everything was suddenly cast into harsh brightness.

But when his eyes had adjusted another shock awaited him. His pyjama top, his face and the backs of his hands were spattered with reddish brown marks. He looked down, first at his hands, then pulled his jacket away from his body and looked at that. It could have been gravy. It could have been a very ripe old red wine. But instinctively he knew what it was. It was blood.

It struck him at once that he urgently needed to know if he was bleeding, but after checking all the likely sources, including unbuttoning his jacket he was satisfied that he wasn’t. The comfort that brought him was short-lived. Because there really was quite a lot of the stuff. So where had it come from?

He needed a cup of tea. And he needed something to fill the terrible silence of the house. So he made his way down the stairs to the kitchen. As he passed the telephone table he saw the keys glinting in their bowl. He let out an involuntary sigh. Oh no!

The kitchen held another surprise as he took the kettle to the sink tap. There, in the basin, was the long kitchen knife, part of a set that usually hung from a magnetic strip on the wall. The blade of the knife and the handle were streaked with what could only be wet blood. He almost dropped the kettle but held his grip and filled it instead, his mind churning now with incoherent thoughts.

Mug of tea in hand, he went to his favourite chair in the living room and, picking up the remote, flicked on the TV. A rolling news programme filled the screen. The presenter was just finishing the main bulletin and announced to the camera, “And now the news from your own region…”. A new face took over and announced that a body had been discovered in the early hours of the morning. They gave the name of the town. It was his town. The picture changed to a outside broadcast in which a raincoated man stood in front of a scene lit by glaring halogen lights as uniformed and white clad figures moved urgently to and fro. The dead man, he announced, was a youth in his late teens who had suffered a sustained knife attack and had died at the scene.

The camera panned away from the raincoat and he saw to his horror a place he knew too well. It was the mouth of the subway that he had used that very morning. The man on the TV was still talking “… trying to identify the victim. A thorough search is underway for the murder weapon…” His hand shaking, he picked up the remote and turned the set off. Could it be… could it… How?”

Rising unsteadily he crossed to the door of the study, went in and sat down in the seat. He reached for the power switch on the PC but drew back, now afraid of what he might find. Then he pressed the button. The machine whirred and buzzed into life and told him that he had two new notifications from his doorcam. His hand was shaking as he typed in his password and the first attempt to do so brought up a warning that he had entered it incorrectly. He cursed and tried again. This time it worked and he opened the doorcam app.

The first clip presented a, by now, familiar scene. The camera swung back as the door on which it was mounted opened, then he passed in front of it in his pyjamas and went down the path. But this time he was holding something limply in his right hand. It caught the light from the porch and glinted, but he could not quite make it out before his figure reached the limits of the camera’s range and disappeared into darkness.

The second clip was much more harrowing. In it, he returned again up the garden path towards the door. It was not a sharp image but again he could see his face horribly devoid of expression. The glinting thing still hung from his hand. But his pyjama jacket and face were now covered with dark blotches.

He ran the clip again and again, not wanting to accept the dawning realisation in his head. The blotches must be the blood stains he had discovered that morning. The glinting thing … could that be the knife now in the sink bowl?

Distractedly, he found some dirt under his fingernails and picked away at it. It was black and greasy, and suddenly he was recalling yesterday’s fall and the dirt in that subway. Then he realised he was still wearing his pyjamas and the thought made his heart race. He hauled himself out of his seat and climbed the stairs as quickly as his old body would allow. In the bathroom he stopped off and ran the shower, scrubbing and scrubbing at himself until his skin tingled.

When he was dressed, he bundled his pyjamas into the washing machine and set it to wash. Reaching under the sink he found a scouring pad and went to work on the knife. In his head there was a deep foreboding that he could not shift. Suppose it was right? Suppose he had killed that kid. In his sleep, maybe, but still that was what it looked like. And suppose someone saw him while he was out, knife in hand? Suppose someone else had a doorcam or a security camera? Suppose he’d been seen? He tried to rule it out of his mind but it refused to go. It all made sense. An awful, threatening, unknowable sense.

He looked down at the knife. The blade was now clean but the wooden handle, where the lacquer had long since worn off, bore dark stains that seemed to have soaked in. Scouring only produced scratches in the surface of the wood. Frustrated, he tossed the knife back in the bowl. He’d have another go later and if that failed he’d just have to get rid of the thing.

Then another thought struck him. His own doorcam. He was worried someone else’s camera had caught him but here he was, harbouring evidence against himself. Get rid of it now. Wipe it. Nobody would need to know. He went back into the study and again attempted to fire up the PC. But by now his mind was so clogged up with all these imaginings that he could not be sure of his password. Each time he tried, the error message came up until, after the fourth attempt the message changed. It now warned him that he had made too many attempts and if he got it wrong again he would be locked out. Now he remembered something his son had said when setting the thing up: that there were so many scam-artists out there trying to take over your PC, so he’d set the lockout threshold at 5. He’d made some effort to protest at the time but his son had insisted, better safe than sorry. The worst that could happen was that he’d be locked out for 24 hours which would be enough time to remember his password. So damned rational, the boy, you couldn’t defeat him in an argument.

He tried to calm himself with some deep breaths then addressed the keyboard one last time, summoning up all his concentration, and this time, thankfully, one painful character at a time, it worked. Immediately, he went again into the app and tried to find out how to delete the clips. After half an hour, he gave up without success. There must be a way but he was damned if he could find it. So he shut the PC down and returned to the kitchen, where the washing machine was going through its final rinse cycle before working itself into a frenzy of spinning.

He stood before it watching in something between a daze and a trance, like a mesmerised cat, until the drum slowed then stopped and the door lock released with a self-important click. His mind was still raking over what he had seen and what sense he could make of it when he hauled out his damp pyjamas and, opening up the airer, draped them over to dry.

He took himself again to the chair in the living room where, again, he fell into an exhausted sleep. But this time it was not a peaceful sleep and he woke, sweating, several hours later with strong images of walks through dark streets and vicious confrontations with hooded figures, a glinting knife swishing before him and tearing into them. Was this just a dream or a recollection? It all seemed so real.

He decided that enough was enough and when he went up to bed that night, after carefully locking up and this time putting the keys in a Tupperware box in the freezer, he took with him some strong nylon string and tied his right ankle to the bed post before lying back and attempting to sleep.

He woke as he hit the bedroom floor, his legs still up in the air. As he did, he felt the warmth of his pee spread over his belly. Shaken, he lay there for a while trying to work out where he was and how he had come to be there, then slowly remembering that he had tied himself down the previous night. The ridiculousness of the situation briefly overcame him and he started to laugh but it stopped when he realised how trapped he was by his fall. It took him, it seemed, an hour to edge himself round into a position in which he could claw at the string and untie the knots, after which he fell back on the carpet and fell back to sleep.

Coming to, he scrabbled, with minimal dignity, to sit up and slowly raised himself until he was perched on the edge of the bed. His damp pyjama bottoms reminded him with a waft of urine that he had peed at some point. The shame of lack of control ran through him like an unpleasant wave but still it appeared that he had won over his pattern of sleepwalking. Painfully, realising that he was bruised and wrenched, he reached out for his phone. Instead of grasping it he knocked it and it clattered to the floor, bursting into life. He could see it was 04.23. He left the phone there on the floor. A thought passed through him of days gone by when he could just sleep, God dammit. But then his mind turned again to a cup of tea.

For the second morning in a row, he sat down with a mug of tea before the early morning TV. And here came the “news from where you are”. And there was the perfectly primped presenter informing us that “police have made an arrest in the case of the murdered teenager. It followed the finding of a knife thought to be the murder weapon in a drain close to the scene. The knife bore the fingerprints of the alleged attacker, a teenager fron the same residential community.”

For a few moments, the significance of what the TV had told him did not register. TV can be like that, setting a distance between you and reality. Then he saw what it meant. He hadn’t killed anyone. That was just a fantasy, a fabrication his mind had made up of his own worries. He was in the clear. Whatever the truth was about what had been going on, he hadn’t murdered that boy.

A surge of relief went through him. In that moment it did not matter to him that the boy had died. It only mattered that his death would not be pinned on him. He could not even feel a flash of sadness. All that mattered was that he hadn’t done it.

He felt almost light-hearted as he went upstairs to shower and dress. He made his bed and gathered up his dirty clothes and brought them downstairs to the kitchen. He made himself another mug of tea and a slice of toast. But he was being drawn inexorably back to the PC. Somewhere in his mind he needed to fit what he had seen into the new, safe version of reality that the TV news had offered him. He found himself back in the study, calling up the doorcam app and watching the sequence through, again and again.

The doorbell rang and in the same instant the screen flashed up a new image, the unmistakable uniform of a police officer. He jumped at the sight of it, a fresh wave of guilt surging through him and his face starting to burn.

He didn’t think he had paused for long but the doorbell rang again and this time it was accompanied by an insistent banging on the door.

He didn’t have time to close the PC down, so he rose heavily from his seat and moved out to the hallway, closing the study door behind him. Shuffling to the door, the thought came into his head how much did they know? They couldn’t know anything. There was nothing to know.

The keys were not in the bowl by the telephone. Where the hell…? Then he remembered the freezer. He called through the door “Moment. Can’t find me keys.” As quickly as he could he went to the freezer and retrieved them. They were, unsurprisingly, ice cold and burned his fingers. All the while he was trying to remind himself “Nothing wrong. You’ve done nothing wrong.”

He drew back the bolts, offering to the person on the other side of the door what he hoped would be a conciliatory “Hang on, just unlocking…”, then turned the key in the mortice and unsnibbed the Yale.

Not one but two police officers stood before him in the porch, each looking so young and fresh-faced they could have been dressed-up schoolboys. One of them had a notebook open in his hand, a pen poised in the other. The other officer did the speaking.

“Sorry to bother you, sir, but I don’t know if you are aware of an incident in the neighbourhood two nights ago?”

“Incident? You mean that boy? I thought you’d caught the man who did that.”

“We are just carrying out enquiries, sir, in case anyone saw anything.”

“I, er, I live alone here. Don’t, don’t get out much any more. Keep meself to meself. Sorry. Don’t think…”

The officer cut in. “I notice you have a door camera, sir. Just wondering if we could take a look? It might have picked up something … or someone.”

He paused trying to think what to say. The officer jumped back in.

“Perhaps we could just step in and take a look, sir? If you don’t mind? Won’t take a minute.”

He didn’t know why he was feeling this way. He knew he was in the clear but looking at them he didn’t feel it anymore. If they saw the stuff on the PC they’d be bound to ask questions. He tried to think quickly.

“Could you come back? Only I’ve got something on the go in the kitchen.”

“Won’t take a moment, sir. We can take a look while your attend to, er …”

Unable to come up with any further excuses, he stepped back resignedly, widening the entrance, mumbling, “S’pose you’d better come in, then.”

They stepped over the threshold, each in turn making a big show of wiping his boots on the mat. He led them the few steps down the passage and signalled at the door of the study. “It’s in there,” continuing into the kitchen to make himself look busy.

A couple of minutes passed during which he swiftly filled a saucepan and plopped two eggs into it, lighting the gas under it. Then one of the officers put his head around the door. “Sorry to interrupt, sir, but we need your password to get in.”

“Oh, oh yes. It’s timed out again, has it? Does that.”

How could he stop them finding the stuff? Think of something.

He shambled past the officer who followed him back into the study, where his colleague was sitting in the chair, mouse in hand, staring at a dialog box demanding a password. The officer rose swiftly as he entered and stood aside. The tiny room felt over full and vaguely threatening now.

But the sight of the dialog box as he took the seat triggered an idea. He paused as if trying to think then ponderously typed a string of characters. The box filled with asterisks. He paused again, as if to confirm to himself what he had typed, then pressed the return key. Immediately the box threw up a message in red “Incorrect password. Try again.” He uttered, “Damn!” and repeated his actions. The same message flashed up. The officers shuffled edgily behind him.

“Sorry,” he said, “Getting flustered. I could have sworn that was it.”

“Take your time, sir,” said one of them in an attempt to sound soothing.

“Can one of you go and rescue me eggs? On the stove?” The one nearest the door left the room as bidden.

“I … I’m sure it’s this. I only used it this morning…” Again, the error message. He counted in his head. That was three. He made another attempt, trying not to show any sign of being pleased with his deception. And yet again the message came up. He could feel, behind him, the officer getting more impatient but trying not to show it.

“Have you got it written down anywhere?”

He shook his head. “Me son told me on no account do that. I told you, it was working this morning. Can’t understand…” That was four. One more should do it. And slowly, pausing over each key, using only one finger, with the same force he would have used to poke an obtuse individual in the chest he punched in another attempt. This time when he pressed enter a different message came up: “This task is temporarily unavailable because an incorrect password was entered too many times. Please try again later.”

He allowed himself what he hoped would be a convincing curse and slammed his fists onto the desk, then swivelled to face the officer standing behind him. “Bloody thing. I’m sure it did it right. Sorry. Can you come back later?”

The officer tried an accepting shrug.

He felt a burst of relief and hoped it didn’t show in his expression.

“After all, it can’t be all that urgent now, can it? Now you’ve got the bloke?”

“Oh, no, sir. Sorry. Bit of a misunderstanding, I think. We’re not investigating the murder, sir. Something else. Rather nasty in fact. Seems a neighbour’s dog was attacked and killed. With a knife. Big knife. Very messy. Brutal, I’d call it. Neighbour’s very distraught of course. Found the dog in the morning, lying in a heap.”

The door opened and the other officer returned. But this time he was wearing disposable gloves and holding two clear plastic bags. In one was the pyjama jacket from the airer but even through the packaging he could still make out dark areas of staining on it. In the other was the kitchen knife. “Found this in the sink. Can I ask, sir, when did you last have occasion to use it and what for?”

I have felt uncomfortable about the treatment handed out to Kevin Spacey ever since the dogs were loosed from their cages. That is not to say that I do not have sympathy for his alleged victims or that I think he did no wrong. It is because it struck me from the outset that he, as much as anyone, was in need of help and support and that the knee-jerk, manufactured outrage from a press in search of another famous head to roll in pursuit of a quick profit was not going to help anyone. It rarely if ever does.

I do not, I need to stress, seek to belittle the experiences of those alleged victims and I certainly do not intend to suggest that they should just “get over it”, “man up” or any of the many other phrases that have at times been deployed to attempt to whitewash their traumas.

Nor do I take the view that Mr Stacey’s undoubted “greatness” in his fields – acting, directing, turning things round – should bestow on him a kind of immunity from the standards of behaviour that the less-worthy rest of us are expected to adhere to. But I do feel that the criminal court and legal actions in pursuit of massive financial reparation are the wrong ways to address his issues.

Credentials time. Which again I must caveat. These are things that actually happened to me during my life. I am aware that each of them had an impact at the time and that each continues to send shockwaves down the decades but I have just carried on: but not because I am specially brave or strong, simply because that is what we did. It wasn’t right. And I do not expect anyone to emulate me. Please God, no. But how much harm did it actually do me? I don’t know. But would I want any of the perpetrators hounded for what they did? No. That should be, and is, my decision.

I have been kissed on the lips by three men in the last 40 years. To none of them I consented, nor, to my knowledge, gave any invitation. None of them actually asked before doing it. If they had I would probably have said no. Not, specifically, because they were men but because I had no wish to kiss them. At the time the first kiss happened I was so much of a virgin that I had not kissed anyone on the lips. At the time of the second, I had only recently lost my virginity and experienced my first passionate kiss, with, as it happened, a woman. In the third case, though the perpetrator of the kiss had been very clear about his “bisexuality” and had given to me a very vivid, third-pint-of-beer, picture of how he wished he could help me to learn to go down on him, and though I had not balked at his discourse, I had been, I thought, pretty clear that I was not ready for such activity, which I had thought he had accepted.

What about power differentials? The first was younger than me by a couple of years. We were both pupil barristers. I thought he was heterosexual – which amounted then to knowing that he had a girlfriend. He had barrels more self-confidence than I had, but then I had seen garden sparrows with more self-confidence than I had. What shook me was the sudden blatantness of it. One minute we were walking through the passageways at Holborn Station talking slightly inebriated stuff about the forthcoming Christmas, the next moment his lips were pressed to mine and his beard was scratching my chin. Then he said “Bye” and left.

The second was older than I was by a few years, and, to be fair, I had been “warned” that he was gay. But up until the minute when he pushed his face into mine I had had no intimation that he was in any way interested in me. And he probably wasn’t. Thankfully, within moments, the rest of the party caught up with us and again it was over (except in my head, where it has stuck to this day).

I have already covered the third male. A good man. “He meant no harm by it.”

Is that it? Is that the sum of it? Not really. In my late sixties, I reconnected with an old school friend from fifty years before. He had been the first person I actually knew who was homosexual, and that at a time when active homosexuality was a criminal offence. Like many boys of our age, we messed around together in ways that would have been frowned on but I had neither the insight nor imagination to think it reflected upon who I actually was and where I stood on any as yet undiscovered spectrum. The idea hadn’t reached Wanstead. And in any event, he had a girlfriend whom he flaunted with regular allusions to sexual activity. But when we met again, a few years back, he had had a lifetime of same-sex relationships and I had only had a few meagre years of failed liaisons with women. Yet he took it upon himself to lecture me on how I loved him and had always loved him and for a while was quite strongly determined that we should fulfil this with some immediate bedding.

I think I actually found this more shocking, more threatening and more disturbing than the other two events. I was stronger and more confident by now but the insistence of it – the insistence that he knew, and was telling me, how I felt about him – made me feel small and vulnerable. It was as if I did not exist except as his image of me. Part of my problem was that I did not want to hurt or dismiss him or be forced into a feeling of outrage at his insinuation. I did not want to seem homophobic and I did not know how to respond.

All three of these experiences go against the grain of my experiences with other gay people, who have been kind and decent and shown no inclination to push beyond that. It is not that gay people are better than non-gays. It is that they have their preferences and choices and loves just as heterosexuals have. Despite all our efforts over the years to disparage them, to parody them as sexually incontinent and predatory, they and we are one and the same. I have only recently lost a dear friend who was gay and in a stable relationship for decades but who always made time to meet me for lunches and conversation but never for a moment made me feel uncomfortable in his company. And my experiences among heterosexuals have not been exemplary either. I have only once been groped and that was in a pub by a rather inebriated woman. She giggled and insisted that I “had a nice bum” and she “couldn’t resist”. I wondered how it would have panned out if I had been a young girl and she had been a man.

But traumas? No. If you want a good trauma, how about this, from when I was about five years old and painfully shy. My mother took me for a check-up at the local surgery. The doctor was someone I didn’t know. They talked over my head. I was just expected to strip down to my vest and pants and endure his poking and proddings. I was the specimen. Then, without warning or any seeking of permission, he pulled the elasticated waistband of my pants away from my stomach and peered down at my genitals. My mother leaned in to take a look too. In the embarrassment of the moment my sphincter relaxed and I watched in horror as some urine dripped from my tiny penis. My mother and this doctor watched too. Then he let go of the elastic, told my mother everything looked normal and carried on. I was mortified. I still am.

Now, that has stayed with me for 68 years and counting. It still makes me squirm. I don’t know how much harm it did but at the age of 31 I was still completely unable to contemplate being undressed in the company of others and frankly I still am.

Would it help me to have the damned doctor prosecuted and condemned, to have his job and pension taken away? No. Would it help me to do the same to any of the others? No. Maybe a recognition that they had acted out of turn would have helped but I suspect not much. No, just as a child cannot unsee the moment when his parents died in front of him, the unspeakable grief haunting him for the rest of his life, the idea that I could achieve the undoing of all these insults to the sanctity of my self by bringing down the law on their heads is phoney. It is the futile reaction of a society wanting to bring restitution but only being capable of breaking more crockery.

Even if I had been raped, physically violated, the incarceration of my predator would not have brought even the remotest semblance of justice to bear. The best it could do, if he was still a threat, would be to neutralise that threat: to put him beyond doing more harm.

Back to Mr Spacey. No-one has said he raped anyone. But no-one, including himself, can say that he behaved appropriately to any of the people he is alleged to have abused. So far as I can tell, like me, none of them invited the behaviour. And if it occurred, each one of them was entitled, as a human being, not to have it inflicted upon them without their consent. I think most of us can agree on that. But can anyone tell me what positive purpose would be served by locking him up? What purpose has been served by taking away his career? By setting him up as a pariah? Doesn’t that just make us feel good about ourselves? Something we would be hard pressed to justify. Let he who is without sin…

No, what it seems to me is that Mr Spacey needs is therapy (as do his alleged victims) and supervision. The therapy, need I say, should not be about changing his sexual proclivities. Those are what they are and he is not only entitled to them; they are a part of what he is. No, what he needs to come to terms with is the need to respect the people around him no matter how attracted to them he is. He needs to learn how to approach the issues of attraction, interrogation and consent.

I had to. When my daughter reached 13, I was left to bring her up alone. I was already fifty years old, a defeated, frustrated male. She had her friends. They were innocents on the cusp of womanhood. It would have been easy for me to use the difference in our ages and status to overwhelm them, to predate upon them. I didn’t. And it took every ounce of self-discipline I had in some cases. It was a daily battle. But I succeeded. Sometimes I wish I had failed but I know it would have brought me – and them – no lasting pleasure. It would have been wrong, and fortunately I knew it.

I may be wrong now but I rather doubt whether Mr Spacey ever saw himself as the entitled male lording it over his subjects, expecting and demanding fulfilment. I am unpersuaded by anything that I have heard as to whether there was anything malevolent in it. My guess is that his actions were hallmarked first by simple desire, then by uncertainty masking itself in bravado born of a long-held belief that he must not show weakness. But I don’t know. It seems he got it wrong, but who among us has not at some point?

A part of his problem seems to have been the pressure on him to keep his real nature under wraps. That was our fault. We made people like him build webs of deceit to disguise who they were. We wanted the American dream: a sexless Barbie-and-Ken world of perpetual consumerist bliss. And we sacrificed the people who actually feel things on that altar. Then, when we caught these noble spiders in the web we had made them weave we brought the hammer crashing down upon their poor heads.

It is not for me to forgive Kevin Spacey His trespasses. That right belongs solely to those he trespassed upon. But I long for a world that doesn’t seek his crucifixion just in order that we might enter our own version of heaven.

It is a month, almost to the day, since my daughter and her partner moved out of this little house.

She had been living with me for 13 years, half her life, since her mother left to live and work in the US. Her partner, G, had come to live with us four years ago, in rather extraordinary circumstances that I do not need to go into but, in 2020, COVID brought new restrictions for everyone (except, it seems, Boris Johnson and Dominic Cummings) and, by the time those ended, his presence in the house had become an established fact.

We actually rubbed along quite well but it did not prevent a certain level of curmudgeonly resentment from building in my mind. G was a good cook and liked to cook as a relaxation from his day job as a bricklayer. Up until his arrival I had been the provider of food and had achieved a level of competence in a narrow but useful range of meals, but after he moved in my role was limited to forager and banker, which I found less satisfying for all that it was still demanding.

To find resentment in someone making your life better is pretty sad but it wasn’t just the diminution in my role that I resented. Still, to list all the petty grievances that surfaced in my head over the period would serve no purpose here but to make you, the reader, squirm at my insufferable intolerance so I shall refrain from doing so but let me say that even as they arose I knew that they were simply the hooks on which I hung my ego’s discomfort.

All of which did not stop me from recounting them to anyone who would listen, most often in the pub, which I visited regularly out of what I liked to think of as a sense of duty. But as I told my tale of woe it always elicited the same response from my audience: “Throw them out. Give them notice then chuck their stuff into the garden and change the locks.” And as soon as this advice issued forth, I knew that I had done a bad thing. It was a self-serving lie.

Because it really wasn’t that bad at all. Yes, it was less than ideal but it was not their fault. They wanted a place of their own just as much as I wanted my space back. They just had nowhere else to be. And I had the room to offer them. In my heart I knew that what was happening was The Right Thing To Do. Throwing them out, even asking them to leave, even letting them know that I would like them to leave, would have been an offence against decency. So I swallowed my resentment and got on with … getting on.

Not, of course, that this put a stop to my craving for their departure, or my displeasure and the hundred and one little “inconveniences” that their presence put me to. No, these worked themselves up in my head on a daily basis until I could barely contain them.

So it was a huge relief when they announced that they were actively looking for a place to move out to and an even greater one when they found a place. I tempered my joy at their imminent departure with the thought that it was as good for them as it was for me and threw myself into helping them complete the move.

As I said at the start, it has now been a month since they moved out. And here I am, in the middle of the night, unable to sleep. And a good part of that inability is down to the unnatural quiet of my home. The almost supernatural awareness that I am alone here heightens my sensitivity to almost any sound that a house makes at night as it cools. But it is more than the sounds of silence. I no longer come down in the morning to a sofa that needs straightening because my daughter has been sitting on it. I no longer have to collect dustpans full of cement and brick dust from the lobby on a daily basis. The coatracks are empty of all but my coats and hats. The TV, which for years I regarded as under the narrow jurisdiction of my daughter’s tastes, now demonstrates to me repeatedly that there is nothing that I want to watch. “My” music, which, for years, I told myself I could not play because it would not be “appreciated”, now jars and irritates me when I switch it on.

I suppose in time I will reach a new accommodation with myself and learn again to live alone. But, for now, I am experiencing something akin to grief at the loss of the company that I had, for some time, enjoyed the luxury of believing had been imposed on me.

The truth of that old adage is glaring at me. Be careful what you wish for.

A rather trivial little poem for Earth Day 2024

What on earth gave us the right

To run the show both day and night?

Who said “we’ll take whatever’s needed”?

Oh yes, of course, we did.

What on earth made us so cocky

To drag the world down roads so rocky?

Who ignored the few who pleaded?

Oh yes, of course, we did.

What on earth do we think we’re doing

Shutting our eyes to all the ruin?

Who told us we can’t be defeated?

Oh yes, of course, we did.

What on earth can save us now?

Not fossil fuels or or sacred cows.

No, we must reap the fields we seeded.

What brought us to the brink? We did.

We had the great good fortune to study some of William Butler Yeats’ wonderful poetry at Wanstead High School in the late sixties. At the time it meant little to us and simply gave scope to schoolboy invention. I particularly recall “Who Rides with Fergus Fish” and how farts became known as “The Wind among the Reders” in honour of one of our class who was noted for them.

This one has been adapted, without permission of course, to reflect more accurately life as we know it.

Had I the heaven’s embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light;

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my jeans;

I have spread my jeans under your feet;

Tread softly because the landlady doesn’t allow visitors after ten fifteen.

I have been told on occasions that my posts are “too personal”. So here is a “trigger warning”. This contains personal stuff. I am neither proud nor ashamed of what follows. It was what it was.

She called me Schnucki. It wasn’t my real name, it had been the name of my sister’s dog. A pet name, then, in more than one sense.

At the time it just seemed charming to me. I was in love. I needed to believe she loved me. So I embraced the name as any lover would. It has only recently occurred to me that in bestowing on me the name of a pet dog she was making a point, a joke.

Oh, but she was lovely. In winter she wore long Liberty skirts over knee length black boots and a crushed velour hunting jacket over a silk blouse, In summer it was Laura Ashley print dresses (God, I’m starting to sound like Sally Rooney). She looked like a Russian princess as she strode around and I fell hopelessly in love with her.

There’s a cliché right there – “hopelessly in love”. But the thing about cliches is that they have their origins in truth. I was 31. I was still living at home. I had yet to kiss anyone other than my Mum and a few Aunties up in Sheffield (obligatory pecks on cheeks). I had “fallen in love” just once before, at the age of 15 and had managed to persuade myself that that was it, the one true love of a lifetime (I was a romantic, into Mahler and Cohen), which I managed to scupper by long bouts of brooding silence and total, platonic immobility over several years. Yes, as it awakened in me, it felt hopeless.

But somehow, this time I worked myself into a state in which I had to tell her and I did. We worked about two floors apart and one evening I went in search of her and to my utter surprise she said “Let’s go for a drink”.

In the Two Chairmen, one drink became two then three and I found myself talking, quietly but with the unexpected aura of confidence, telling her about me and then responding to what she said about herself. I knew next to nothing about her when we entered but those drinks opened us both up and she seemed genuinely to want my take on her issues while I heard myself uttering a kind of quiet savant wisdom that I hadn’t known I possessed until then.

I told her I had fallen in love with her and she suggested that we walked across the road to St James’s Park. It was dark by then. She seemed amused when I said I had never kissed a woman and suggested I should kiss her. And I found myself kissing her and felt her warm and responsive in my arms (God help me, it sounds even more like Sally Rooney now).

At some point we both realised that my hand was on her breast, something I had never done before, had never thought I could do without repelling the person I was touching, but she just laughed softly and said “Found them alright then.” And that took away all my guilt. I was in love. Everything was suddenly “as it should be”.

Then she told me about her husband.

It was beyond strange. She spoke of him with huge respect and affection and I remember thinking “Then what are you doing here with me?” But I wanted it to go on so, like Pinocchio, I knocked Jiminy Cricket off my shoulder and carried on. From now on, I was a real boy.

I think it was a few weeks later that I was introduced to him. We had all been working late and met for an after- work drink. And I liked him immediately. Not only was he clearly the most intelligent man I had ever met, he was also gentle and kind and he clearly adored her and welcomed me unquestioningly. The pangs of conscience were audible now in my head but they were not loud enough, yet, to persuade me to stop. We walked to Victoria Station and, on the pretext of having to see me to the other platform, she left him on the Westbound side and walked with me through the subway to the Eastbound platform, stopping in the middle for a passionate kiss. I saw what “shining eyes” meant. Hers were positively blazing with what I was keen to read as joy.

For the next little while it was a passionate relationship. She took me to her bed and ended my virginity. No really, that’s how it was. We had taken the afternoon off and ridden the tube to the end of London where their house was. There she excused herself and went upstairs. I, naively unaware, sat on the sofa wondering how long she would be. Then after five long minutes she called down, “Well? Are you coming up?” Puzzled, I climbed the stairs and found her naked in bed. I had never seen a grown woman naked before except in photographs. She seemed entirely comfortable, however, and when she told me to get undressed I complied, in an instant setting aside all the shy reserve of thirty years (up to then I didn’t even like having the top button of my shirt undone). She told me later, in a kind of benign feedback session, that I should never leave my socks til last, it was unattractive. It was as if she was training me. I realise now that she was. I was her project.

I can’t recall much foreplay. My penis became instantly, painfully hard and, as if a program had been activated without involving me, it found her opening and slipped inside. I came immediately. She said, with no malice, just a teasing smirk, “Is that it then?”

All at once I was consumed with a panicked guilt. She read it in my face immediately and asked me what was wrong. I blurted out my fear that I had made her pregnant. She laughed, gently, and told me that she wasn’t up for taking risks like that and then explained to me about the Dutch cap that she was wearing. This was all new to me. Another learning experience. Another pair of words for my lexicon.

I was, from that time on, through all my years to come, until Finasteride and Tamsulosin relieved me of any vestige of sexual competence, a useless lover, always premature, always trying in the heat of the moment to work out how to please, never quite succeeding, always clumsy and embarrassed. But she did not complain as long as I tried. She was like a patient teacher with a backward child. We had evenings together (but never nights) and she introduced me to smoked salmon and cream cheese and champagne (“You have to love The Widow (Veuve Cliquot), such a happy champagne”, though sometimes it was Perrier Jouet with its fancy embossed bottles and once or twice pink, when strawberries were in season.)

Then there were the evenings out with both of them. They introduced me to the Cork and Bottle, then in its heyday, and I got to meet Don Hewitson and to become acceptably pretentious about wine. And the more I got to know her husband the more I liked him, which was awkward. But his gentle acceptance of me allowed me to think that maybe, just maybe, this was okay, that in some way I was making things better. I tried not to think about whether he knew or guessed what was going on and I learned instead to play the part of a flattering and appreciative friend.

Looking back now it sounds like Pygmalion with me cast as Eliza. I grew in sophistication and, like Miss Doolittle, began to believe that this newly educated version of me was the real thing, not just a social experiment.

For their part, they seemed to want my company, both of them. And through them my horizons broadened, through classical concerts, dinners, conversations, wine tastings. I say they broadened but again I now see how much of the tunnel of my life was closing behind me at the same time as it opened in front of me. My school friends now seemed dull and horribly prosaic. They had no interest in my accounts of things I had eaten and drunk and I was aware that their lives meant little to me. Things I had enjoyed now palled, no space. The same became true of my relations with my parents, who had up til then seemed so inspiring but now seemed so narrow and even judgmental (as indeed was I now, though, of course, my judgmentalism was righteous).

But all that mattered at the time was the approval of this woman and her husband. For that I learned to shine before their shiny friends and to enhance any social gathering they took me to. She said to me one time after I had risen early to tidy the last night’s abandoned party “Schnucki, you are the perfect house guest.”

But I was learning something else too, something that a perfect house guest must never lose sight of: that you are at best an adjunct, an accessory. Never believe that you are more than a part of their story, an anecdote, an amuse bouche for their table.

I had become aware that I was not her only lover. She had at least one and sometimes more than one other. And much as it hurt me to realise it, I saw that I was not even Number One lover. But such was my fear of losing her, of losing what she allowed me, that I took this on board even to the extent of becoming her confidant and counsellor as she tried to manage the deceptions. “Hide in plain sight”. “Only deviate from the truth as far as is strictly necessary.” I was learning to see morality as an exercise in pragmatism rather than a set of strict commandments.

I could not see what she saw in this braying Ulsterman for whom she was just a bit on the side but it offered nothing to question her wisdom. I was a card in a house of cards and if one of us fell we all would.

I failed to realise her ambition for me until it was too late. She wanted me to leave home. This was my test. I had to move away from the comfort that I had been taking for granted. So, to please her, I went in search of a flat. This was the Eighties, I could afford it. And I was spurred on by the thought of the heated afternoons we would have there, drinking champagne and fucking.

It had to be central and I found a flat in Pimlico, ten minutes’ walk from the office.

On the day I moved in, she came to my office and demanded to know what I was going to cook for myself that evening. I hadn’t given it a moment’s thought. Food was what my mother always provided when we men got home from work.

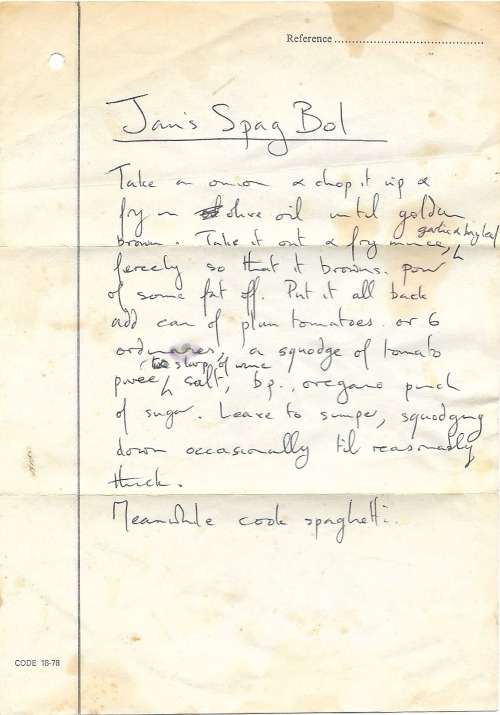

Seeing my bewilderment, she said, “Right, Schnucki, write this down.” And she dictated a recipe for spaghetti bolognese (I still have it. Any of you inclined to sneer at the inauthenticity might remember that this was the early 1980s. My Mum didn’t even use garlic, or basil. I make a modified version now.

).

On the way home to my new abode, I stopped off at Sainsbury’s and picked up everything on the list, then went home and dutifully made the thing. It was good. The next day she quizzed me on it and seemed content.

It was only much later that it dawned on me that this was the closing chapter of her project. Job done. She never visited me in that flat. We never made love again. In time, when I met the woman who was to become my wife and the mother of our children, we stopped seeing each other altogether. It hurt, yes it hurt. At the time it felt as if I had been dropped from a great height into an empty sea. I wondered what I had done wrong. My depression (a thing I had lived with since school but never understood until she had explained it to me) kicked in big time. My Pimlico flat of so much promise became a prison cell. It was only later that I saw the extent of the gift she had given me.

Reading it over, this all sounds a bit cynical and resentful. It isn’t. Can I just say that? The time I had with Jan, what she taught me, and more, so much more, what she saw in me and brought out of me, made a massive difference to how I lived and met the world from then on. It enabled me to find a partner and to father two children who still have the power to astonish me. I am still learning from it. It is no exaggeration to say that she rescued me and set me free and I will always be indebted to her.

The next to last time we met I said to her that I would always love her. And she paused then said “Yes, I think you will.”

And the last time we met, by chance, twenty years ago now, she as radiantly beautiful as ever, me now greying and a bit paunchy, she said, approvingly, like a master giving his dog an appreciative pat on the head, “You said you’d always love me.”

Good dog. Good boy, Schnucki. Good dog.

Actually, not pillows. I want to sound off about cushions. In essence, why do they exist and why did it suddenly become fashionable to strew them about everywhere, making it impossible to sit in a chair or on a sofa or lie on a bed?

I know, there have always been cushions. Well, maybe not always, but for a very long time. But until recently, their purpose has been to lend comfort to hard surfaces or support to resting bodies. They had, in short, utility. I am also aware that some cushions were made to serve another purpose, that of reflecting the taste or status of the owner, a purpose which was, at times, at odds with their primary purpose as their heavily embroidered motifs rendered them uncomfortable against the skin.

But that was little more than an aberration when compared with the present fixation which serves only to render furniture designed to accommodate human bodies unavailable to them.

You cannot enter a hotel bedroom these days without being confronted by rows of these smug, unyielding fabric balloons taking up the bed that you have paid to occupy. They seem to serve no purpose other than to frustrate your desire to lie down. So your first task is to shift them. But immediately that brings you face to face with the existential question, “where shall I put them?” Do you consign them to the floor, like banished dogs? Do you line them up against the wall, like prisoners before a firing squad? Do you cram them into the already inadequate wardrobe? Whichever course you opt for, you are aware that you are being put to unnecessary effort. You are now the slave to someone else’s conception of taste.

And for what purpose? They have no practical use and barely offer any ornament. They are just a self-indulgence by some “interior designer”.

But this awful embellishment has now crept, like a fungus, out of the hotel and into the houses of actual people. It has got so bad that what used to be a practical welcoming gesture “why don’t you sit comfortably on the sofa” calls for the response “because there is no room to do so”.

The alert host may note your predicament and offer a casual, “Oh just move those” – meaning those fat, encroaching cushions presently taking up every inch of the seat. And, once again, immediately, you are faced with a heightened version of the hotel bed scenario. Why should you have to? And where do you move them to? Which, itself, now contains the more delicate question: what level of consideration is owed to these bloated carcasses when clearly your host has gone to a significant amount of trouble to bring them into his or her home and fill every available piece of sitting accommodation with them. You cannot just toss them indifferently onto the floor as you might in the privacy of your rented suite.

So, like as not, you end up perched insecurely on the edge of the said sofa, your clenched thighs devoted to keeping a mere inch or two of your buttocks in place so that you don’t slide gracelessly to the floor.

Is this some kind of covert power play by your host? The living room equivalent of your boss offering you a low seat in front of his grand desk? Is it a subtle sign that you are there on sufferance; not in fact welcome and not to take your ease?

Or do the cushions reflect some deeper psychological affliction? Are they perhaps substitute children, as pet dogs and cats used to be? Larger and more intrusive cabbage dolls or flour babies? You cannot help but wonder where you stand in the pecking order of your host’s mind if a set of unyielding, micro-fibre-filled, fancy cotton bags take precedence over the obligation to give you somewhere to sit.

I imagine that this fad will eventually run its course, and I cannot wait for that day, but I do wonder what will replace it. Will the beanbag, that exquisitely uncomfortable toy of the middle classes in the seventies, make an unwelcome comeback? The time for its rehabilitation must be near. Everything else has gone to pot.

But I can assure you that if you come to my house you will find chairs and sofas that you can relax into and beds that offer you room to stretch your tired limbs. Life is hard enough. I intend to cushion the blow – without cushions.

When we arrived at the hotel bar, after a trying day, we were hoping for a bit of time to unwind and regroup before dinner. We had reckoned without the men, six of them, who had clearly already been there for some time. They had taken over the tables and high stools in the centre of the bar, were well down what may have been, but probably weren’t, their first pints of lager and were well into raucous mutually-affirming badinage.

We had first visited the bar, a part of what was supposed to be a four-star hotel in Taunton, on arrival a few hours before, after a particularly taxing day driving across England to, and the participating in, the funeral of an old friend and colleague. Then, it had only been the music in the bar that had been loud enough to be intrusive but, although it was still audible in the background it could not now compete with the level of sound emanating from this group.

We were booked to eat in the bar – the hotel had graciously allowed that my sister’s well-behaved dog, a nervous and still cowed rescue that couldn’t be shut up and left, could remain with her during the meal but not in the “dining room”. Fair enough, except that the dining room was in fact just an unpartitioned area of the bar. So in fact we had only the options of staying to eat or giving up our reservation in the hope of finding somewhere else that would admit us. And since we had, on arrival at the hotel, been required to provide a substantial deposit towards our evening meal, leaving, without the prospect of a serious argument, was not much of an option.

We had been joined by a friend from the funeral and had been anticipating a gentle conversation with him before going on the eat. Apart from us and the men there were only two other couples in the bar. Twenty minutes later, however, even though we were barely a metre apart, we were each already hoarse with th effort of making ourselves heard over the noise the men, now enthusiastically into a new round of beers, were making,

My only excuse for the interaction that followed, and not a great one, I acknowledge, when the time came for us to take our places for the meal, is that I was aware of how stressful the day had already been for my sister and had wanted this part of it to be as comfortable as possible. I therefore asked if the waitress could find us a table at a greater distance from those men. She looked around haplessly before confirming to us that we could only sit in the bar area “because of the dog”.

I did not react well, I accept this, but I reiterated that we would like to be further away from “those braying drunks”. The waitress, with commendable calm, replied that “they are not drunks. They are just a group of men who have come in aft the end of the working day.” I’m afraid her unwillingness to recognise the deleterious impact of the group riled me somewhat and I responded that if they were not drunk they were giving a good impression of being. She simply stood her ground insisting they were not drunks, just working men and that we had to be in the bar area with them because we had a dog. My reminding her that we were guest of the hotel and that the hotel had assured us when we booked that there would be no problem with accommodating the dog at the meal and that its vaunted mission was to make us comfortable was to no avail.

Fortunately, an hour, and several more beers, later, the men, amid noisy farewells, got down off their stools and left.

I dare say I can guess what some of you are thinking. I should have just got, and should now just get, “over it”, and myself. You will be thinking I was in a bar in a city centre. What did I expect? Why should I think it okay to want to spoil the enjoyment of some working men and why should I think it acceptable to confront a poor harassed waitress in the process? To that last part I put up my hand unequivocally. For as long as I can remember I have understood that, unless the person serving you is behaving obnoxiously from personal choice, you should never allow yourself the luxury of attacking or demeaning them.

I have seen it done so often: inadequate men and women, dress’t in a little brief authority, usually attributable to the overweening size of their bank balances and to the need to demonstrate what they are pleased to think of as their superiority, putting down those whose hapless misfortune is to have to attend to their requirements. Such behaviour is bullying, it is rude and it is indefensible. I am not advocating condescension, noblesse oblige, here. Don’t they know that there are only people in this world and that it is our human duty to treat every last one of them with the respect they deserve, even when you think you deserve better? I “don’t indulge” in such behaviour, or at least I shouldn’t.

All I can say, and my offered excuse rings hollow, believe me, is that my own challenging response was out of character and that it was triggered by a difficult day. And if I could have that time over, I hope I would behave better. But time only works in one direction for humans like us so I can’t go back and do better.

But perhaps, with that out of the way, now we could get back to the point. Those men.

I get that they had been working all day. But did that entitle them to make everyone else’s evening uncomfortable? I don’t think so. Don’t get me wrong. I am no saint, no temperance-driven killjoy. I too have been the worse for wear in bars. But, like it or not, and making due allowance for the reasonable desire to “have a good time”, I believe that nobody should be allowed to have that “good time” at the expense of other people.

It is, I think, a well-identified observation that the volume of noise produced by any group of drinkers rises to meet the level of the loudest member. That certainly is true of men (women, please do not feel left out, you have your own version of this behaviour). I have watched it time and again in the pubs I have visited. Sadly it is also the case that the loudest member of any drinking group tends to get louder the more alcohol he has consumed. Every joke has to be appreciated with a bigger outburst of braying laughter; every anecdote has to be topped by another increasingly inarticulate ramble delivered at full and yet fuller pitch. And so the braying ratchets up.

It is the unhappy lot of the licensee of the premises to exercise control over the behaviour of his customers (I’m not making that up; it is the law). Often a quiet word to the group will be enough to restore order, for the benefit of all and with very little impact on anyone’s fun. Indeed, having been in such groups on numerous occasions I can assure you that I have not been alone in welcoming such interventions. Better that, surely, than to wash one’s hands and allow the unbridled ravings of one man spoil the pleasure of the entire establishment until the whole situation is beyond recall.

Regrettably, some licensees would sooner take the soft option and let duty go hang. It is, of course, false economics because it will, in time, drive away good paying customers but they would rather temporise, kowtow to the drunken braggart, than confront him. It is not in fact limited to drunks in bars. We see the same subservience in other areas of our lives; profit put before people, entitlement raised over the common good, selfishness prized over consideration. Feudalism, which is still the bedrock of our society, always favours the bully. It has become “the British way”.

But it is not how it is supposed to be, nor how it has to be. One man’s, or indeed one group’s, pleasure does not have to be bought with the discomfort of everyone else and we should not be accepting of it. Just a little consideration and accommodation can enable us all to have a good time.

But until we learn that lesson, sadly we will all have to kneel so that some of us can bray.

Image courtesy of The Guardian

As Alan, Ron and I approached the door

Two Brimstone butterflies were brightly dancing.

So out of place. I thought was this a chance thing?

A common sight in meadow or on moor

But here in Basingstoke, at All Saints church?

A sight that made my tired and sad heart lurch

I tried to shed the possibility.

All that occurs has reason if you press

But superstition wants for something less.

I’d pitched my camp on rationality

Yet here’s my heart insisting it’s a sign,

These flitting yellow messengers divine

We’re taught to think of brimstone as God’s wrath,

His anger at the sin of unbelief,

But these two circling angels stemmed my grief

As they paid courtship on the old stone path

And, lifting off the sadness of the day,

They pricked my pompous gloom, blew it away.

Oh, Graham, you and I had walked so far

We’d strode the hills and glens, the moors and sands

I’d found redemption in your gentle hands

Then watched you dwindle like a dying star

I came today to say a last goodbye

And met instead the Brimstone butterfly.

Now in my mind you’re here again, not lost

On this March morning dancing in the sun

Insisting life’s not over, it’s begun

Just open up your heart and let it trust

I feel it now and hopefulness returns

My heart was stone but now a stone that burns.

RIP Graham Osborne, a Good Man.

Iain M Spardagus, 26 March 2024

It was just a door, when it appeared in my head as I lay half asleep.

Just a door, a plain wooden door, unpainted, half glazed, at the end of a short, whitewashed passage just wide enough to contain it and hung with deep shadows where the daylight streaming in through the glass could not reach.

I must have been ten feet or so away from the door. Through the glass I could make out The promise of a summer garden, lawn and mature shrubs, and I had a sense that out there was bathed in hot sun.

Just a door, yet it seemed in my head as I stood before it that there was a whole house behind and around me. I could feel its weight and that there was a time and a place in which it, and I, belonged. Somehow I knew that the time was, and the house was, and the door was, and I was, back sixty to seventy years ago. I searched for some clue to how I knew this but there was nothing. It just was.